2. Scattering, cross sections and decays#

Learning objectives: understand scattering, and the role of form factors, being able to calculate the form factor for simple charge distributions

In this unit we introduce the concept of cross section and show how the measurement of the cross section of an interaction process can be used to study the properties of elementary particles. We also derive cross section formula for the Rutherford scattering and the electron-nucleon scattering. Finally we show how the finite size of the nucleus impacts the electron-nucleon cross section, and we define the form factor that is used to measure the charge distribution inside a nucleus.

2.1. Cross sections#

The cross section is a measurable quantity related to a process in particle and nuclear physics. By measuring cross sections, theory can be compared to experiment. It is the job of the experimental physicists to measure cross sections, and that of the theorists to use models to calculate them. We will use this concept throughout the course, so we introduce it at very beginning, rather than leaving it for later, as some textbooks do.

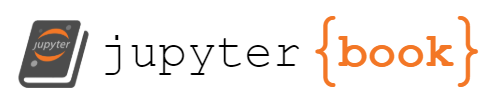

The idea of cross-section arises from the simplest model of a nucleus (or some other particle) as a completely absorbing sphere of cross-sectional area \(\sigma\), as described in figure Fig. 2.1. We define the flux \(J\) as the number of particles per unit time and unit area incident on a thin sheet of material. If there are \(N\) nuclei illuminated by the beam, the effective nuclear area for absorption is \(\sigma_{r} N\).

Fig. 2.1 Diagram showing a beam with a flux \(J\) particles per unit time and unit area on a target with interaction centres of cross section \(\sigma_r\)#

The rate at which particles interact via a specific process indicated by the subscript \(r\) is then

From an experimental point of view, the quantity \(J N\) is defined by the design parameters of the experiment and is referred to as the “luminosity” \(L\) of the experiment. \(W_{r}\) is measured experimentally, as the observed rate of interaction. Using the equation above, we can measure \(\sigma_{r}\), which is a quantity that holds the basic physics of the interaction as it does not depend on the experiment design parameters and can be calculated from theory.

The unit of cross-section used in nuclear and particle interactions is the barn, \(b\), equal to \(10^{-28} \mathrm{~m}^{2}\). In interactions between high energy particles, smaller units such as the millibarn \(\left(\mathrm{mb}=10^{-3} \mathrm{~b}\right)\) or even picobarn \(\left(\mathrm{pb}=10^{-12} \mathrm{~b}\right)\) are often used.

Example 2.1. Alpha particle cross sections on gold.

A gold atom has a nuclear radius of 7 fm . Calculate its geometrical cross section. Compare with the measured cross sections for alpha particles of kinetic energy of 6 MeV scattering above \(30^{\circ}\), which is 157.3 b .

Solution

The geometrical cross section is simply \(\pi R^{2}=154 \times 10^{-30} \mathrm{~m}^{2}=1.54 \mathrm{~b}\)

2.2. Partial and differential cross sections#

In most cases there are several possible reactions between the incident and target particles, and the cross-section for each will be different. These individual crosssections are known as partial cross-sections, and their overall sum is the total crosssection. If \(r\) indicates a specific interaction process, then the total cross section is written as

After a reaction or scattering has occurred the outgoing particles often have an anisotropic distribution, with different rates observed in different angular directions as sketched in figure Fig. 2.2.

Fig. 2.2 Diagram showing the dependence of the cross-section as a function of the angle \(\theta\) and \(\phi\) in polar coordinated.#

The observation of the interaction rate as a function of the scattering angles \((\theta, \phi)\) is used to measure a differential cross section. Then the number of particles scattered per second into the solid angle \(d \Omega\) at coordinates \((\theta, \phi)\) with respect to the incoming beam is written as

where we defined \(\frac{d \sigma_{r}}{d \Omega}(\theta, \phi)\) as the differential cross-section for the process. The measurement of the differential cross-section as a function of the scattering angle will provide further information on the physics processes involved in a specific interaction. For example in the Rutherford scattering, it was the angular dependence of the scattered alpha particle that led to the understanding of the atomic structure.

The total cross-section for a specific process can be obtained by integrating the differential cross-section over all solid angles.

In most cases there is no dependence on the \(\phi\) angle, so the differential cross-section is measured only as a funciton of the angle \(\theta\) and the formula above written as

2.2.1. Reminder: Spherical coordinates in three dimensions#

Working with scattering and other particle interactions we use spherical coordinates in three dimensions. The choice is driven by the fact that processes happen in a specific point in space, such as the location of the target and the observation of a physics phenomenon depends on the location of the detectors in terms of angles.

You have seen a similar set of coordinates being used in other situations where a central potential is considered, for instance in the treatment of the Schödinger equation for a central potential as in the hydrogen atom.

As a reminder, cartesian coordinates are related to spherical coordinates by the transformations (see also figure Fig. 2.3)

Fig. 2.3 Diagram showing the spherical coordinates to be used to change coordinates from cartesian to spherical.#

The solid angle \(\Omega\) is defined in analogy of an angle in the two-dimensional case. A formal definition of the solid angle, according to Wolfram-Alpha is:

“The solid angle \(\Omega\) subtended by a surface \(S\) is defined as the surface area \(\Omega\) of a unit sphere covered by the surface’s projection onto the sphere.”

The solid angle is measured in steradians ( sr ) and a full sphere covers a total of \(4 \pi\) steradians. Referring again to figure 4 we see that the solid angle subtended by a \(d \theta\) and \(d \phi\) element is given by

The corresponding surface element at a distance \(r\) from the centre is

and the corresponding volume element at a distance \(r\) is

Example 2.2. Alpha particle capture cross section

A beam of \(\alpha\) particles with a total current of \(i=10\ \)nA impinges on a thin target of Magnesium-24. The thickness of the target is \(5.75\ \mu \mathrm{m}\), the density of Magnesium-24 is \(\rho=1.74 \times 10^{3}\ \mathrm{~kg} \mathrm{~m}^{-3}\) and the atomic mass is \(M_{A}=24.3\ \mathrm{~g} \mathrm{~mol}^{-1}\). A detector subtending a solid angle of \(2 \times 10^{-3}\) sr records 20 protons per second. If the scattering is isotropic, determine the cross section for the reaction

This example is modelled around exercise 1.14 in [Martin], the goal is to use the concepts presented so far and to introduce some numerical calculations involving cross-sections and interaction rates.

Solution

We use equation (2.1) to work out the cross-section from the rate

The rate that we observe is only a fraction of the total interaction rate, as our detector spans only a fraction of the total solid angle. Rather unusually, the scattering is isotropic, e.g. the rate observed does not depend on the polar coordinates of the detector. Hence the rate observed will be the fraction of the total rate corresponding to the fraction of solid angle spanned by the detector. Or, reversing the argument, the total rate is

We indicate with \(S\) the target area illuminated by the beam, in which case we write the flux as

as the number of particles traveling down the beam per second is equal to the current divided by the charge of each particle, in this case \(2 e\) since \(\alpha\) particles have charge \(+2 e\). The number of particles illuminated by the beam \(N\) can be calculated from the density and thickness of the target and the atomic mass of Magnesium-24

where \((\rho t S)\) is the mass of the target illuminated by the beam, \(M_{A}\) is the atomic mass and \(N_{A}\) the Avogadro number. Hence the value of \(S\) is irrelevant once we multiply

finally putting the numbers in equation (2.1) we have

2.3. Scattering and matrix elements#

The goal of the mathematical formalism of the scattering is to decouple the quantities describing the experimental setup \((J, N, \ldots)\) from the fundamental physics that describes the interaction between particles. In this section, we first reorganise the formula for the flux in a more convenient way, we then relate the rate of interaction to the quantum mechanical theory that describe the fundamental interactions.

2.3.1. Scattering definitions#

Consider the interaction of a beam of particles \(b\) with a target. Referring again to figure Fig. 2.1 , we indicate with \(n_{b}\) the particle density inside the beam, and with \(v_{i}\) the velocity of the beam particles. The number of beam particles that cross a surface of area \(S\) during a time \(\Delta t\) is given by

therefore the flux (e.g. the number of particles per unit surface and unit time) can be rewritten as

where we have defined the volume \(V=1 / n_{b}\) as the volume occupied by each of the beam particles. We should not worry about this quantity as it will cancel out in the following.

For a single particle target, the rate of interaction is given by equation (2.1) as

or in differential terms

2.3.2. Fermi golden rule and matrix element#

The formula derived above provides a way to measure experimentally a differential cross section, by observing the rate of interactions at a given angle. To relate the rate to the physics principles governing the reaction, and hence the quantum mechanics phenomena under study, we need to use the Fermi golden rule.

In quantum mechanics, the value of \(W\) is given by the product of the square of the matrix element \(\mathcal{M}_{f i}\) between the initial (i) and final (f) states and a density of final states factor \(\rho\left(E_{f}\right)\). The matrix element contains all the dynamical features of the interaction such as its strength, energy dependence and angular distribution.

this formula is known as Fermi’s Golden Rule, and is applicable to nuclear reactions, decay processes, atomic transitions, scattering processes, etc. The scattering amplitude (or matrix element) between two quantum mechanical states \(\left|\psi_{i}\right\rangle\) and \(\left| \psi_{f}\right\rangle\) is given by

where \(d^{3} \mathbf{x}\) represents a volume element in space, \(\psi_{i}(\vec{x})\) and \(\psi_{f}(\vec{x})\) are the wavefunction of the initial and final state particles and \(U(\vec{x})\) is the potential energy that describe the interaction.

We use plane wave functions for the incoming and outgoing particles having momenta \(\vec{p}_{i}\) and \(\vec{p}_{f}\), respectively. Thus the two wave functions are

where we have chosen a normalisation factor of \(1 / \sqrt{V}\), as we are expecting to observe one particle inside a volume \(V\). Substituting the plane wavefunctions into the matrix element equation (2.4) we obtain

where we define \(\vec{q}=\vec{p_{f}}-\vec{p_{i}}\) as the momentum transfer in the collision. You can recognise the integral on the right-hand side as the 3-D Fourier transform of the potential energy. We define this Fourier transform as

2.3.3. Density of states#

In the Fermi golden rule the term \(\rho\left(E_{f}\right)\) is the density of final states or phase space factor. The rule applies to quantum mechanical systems where the final states allowed belong to a continuum of states. A transition is more likely to occur if the system has more allowed states into which it can move. For instance, a process where the differential cross section is dominated by the density of states factor is the nuclear beta decay, discussed in depth in the nuclear physics course. We give the expression for the density of states without proof as

Replacing this formula in the Fermi golden rule equation (2.3), together with the cross section dependence of equation (2.2) and the matrix element definition of equations (2.5) and (2.10) we end up with a formula for the differential cross section of

2.4. Elastic scattering in a Coulomb potential#

Scattering particles is at the heart of particle physics as we probe smaller structures. In this section we consider the case where the interaction between the beam particle and the target particle is elastic. This means that the particles in the final state are the same as the particles in the initial state. This scattering regime is achieved for probes with energy \(\leq 100\ \mathrm{MeV}\). As the beam energy increases the target can be excited or broken, and some of the initial energy can be used to produce “new” particles.

2.4.1. Coulomb potential#

In the case of an electromagnetic interaction between a point-like nucleus of charge \(Z e\) and a particle of charge \(z e\), the potential energy is given by

Where \(\vec{r}\) is the distance between the beam particle and the nucleus. From now on, we use \(r\), rather than \(x\) to make it explicit that we are using a spherical coordinate system. This expression will be used for the scattering using alpha-particles as probes \((z=2)\) as well as for the scattering of electrons as probes \((z=-1)\). To evaluate the cross-section we need to evaluate the Fourier transform of the potential as specified in equation (2.7)

The argument of the integral will not have a “good” behaviour for \(r \rightarrow \infty\), so we use a regularisation technique (quite common in field theory), by multiplying the argument by \(e^{-\lambda r}\), where \(\lambda\) is a small positive number. We will then take the limit \(\lambda \rightarrow 0\) in the final result. From a physics point of view, this assumes that the potential energy will decrease to zero at infinity due to material shielding effects. Hence the integral we need to calculate is

The integral is evaluated using polar coordinates as discussed in Section 2.2.1, since there is no explicit dependency on \(\phi\), the integral in \(d \phi\) is trivially \(2 \pi\)

the integral in \(d(\cos \theta)\) is a “simple” integration of an exponential

with another exponential function to integrate, this time in \(r\)

In the limit \(\lambda \rightarrow 0\) the term in the square brackets is much simpler

Finally replacing the expression for \(f\left(\mathbf{q}^{2}\right)\) in equation (2.7) we obtain an expression for the cross-section in the case of elastic scattering in a Coulomb potential

2.4.2. Rutherford scattering#

In the case of the “traditional” Rutherford scattering, we use an alpha-particle as a probe. In this case \(z=2\) and we can assume to be in a non-relativistic regime, with \(v_{i}=v_{f} \ll c\), which means the kinetic energy of the alpha particle is much smaller than its mass \(\left(m_{\alpha} c^{2} \approx 4 \mathrm{GeV}\right)\). Under this approximation the nuclear target does not move and the magnitude of the momentum and of the velocity of the alphaparticle do not change with the collision and can be expressed as a function of the kinetic energy \(\left(E_{K}\right)\)

while the magnitude of the momentum transfer is written as

Replacing this into the general expression for the Coulomb elastic scattering in equation (2.9) we have

2.4.3. Electron scattering on a nucleus#

In the situation when an electron is used as a probe, we can normally assume that the electron will be “ultra-relativistic”, which means \(E \gg m c^{2}\). This is because the mass of the electron is very small \(\left(m c^{2}=0.511\ \mathrm{MeV}\right)\), so an electron with an energy of a few tens of MeV will already be in this ultra-relativistic approximation. In this case the momentum of the electron is related to its energy as

again replacing this into the general expression for the Coulomb elastic scattering in equation (2.9) we have

The scattering of electrons on nuclei is a technique used to study the properties of nuclei, as we will see in the next section.

2.4.4. A bit of history#

The Geiger Marsden experiment, and the Rutherford scattering are well celebrated and important results, which confirmed the atomic structure, with a central charge (the nucleus) surrounded by a cloud of electrons. This was done in 1908, and as we saw earlier the alpha particles did not have sufficient energy to study the structure of the nucleus. Hence the nucleus is considered as a point-like object. To study the structure of the nucleus, shorter De Broglie wavelengths are needed, e.g. particles with higher energy need to be used as a probe. In the 1950s electron beams in the \(>10 \mathrm{MeV}\) range became available, and the nuclear structure could be probed. We will discuss how electron scattering can be used to study the structure of a nucleus in the next section of this unit.

With advancing technology the energy of particles being produced kept increasing, and the scattering is no longer elastic, as it led to nuclear excitations and the production of new particles. The 1950s and 1960s saw a lot of new particles being discovered, which we will study and classify based on the quark model towards the end of the course.

In the 1970s with the use of very high energy electron beams (20 GeV) the structure of the proton could be further studied, showing a substructure for the proton, which is made of quarks. As of today, quarks are still elementary particles, which means that they behave as point-like targets. In the past few decades, particles are collided head on, rather than using a probe to hit a target. The advantage of this approach is that a larger centre-of-mass energy can be achieved, allowing the discovery and the study of the Standard Model particles, such as the W and Z bosons as well as the Higgs boson. We will return on this topic at the end of the course.

2.5. Nuclear charge distribution and form factor#

In the previous section we considered an interaction with a point-like charge. As we increase the momentum transfer of our collisions, we start observing the structure of a nucleus, so we need to drop the assumption that the nuclear charge is point-like. The situation of an electron interacting with a nucleus is shown in Fig. 2.4.

Fig. 2.4 Diagram showing the nuclear charge distribution (grey area). The potential calculated at a point \(\vec{x}\) in space is calculated by integrating over the charge distribution.#

Here we make the assumption that the nuclear charge has a spatial distribution of

Note that we defined \(\rho\) as the charge probability density, which is a different definition from [Martin]. The symbol \(\rho\) is used in many places to indicate “density” quantities. When talking about form factor, we only use \(\rho\) to identify the charge probability density and is a quantity that is normalised to 1, such as

The potential at a generic point \(\vec{x}\) in space is indicated as \(U(\vec{x})\) and to calculate it, we need to integrate over the charge distribution indicated in the grey area of Fig. 2.4. Therefore

The Fourier transform \(f\left(\mathbf{q}^{2}\right)\) of equation (2.10) is calculated by integrating the value of \(U(\vec{x})\) over \(d^{3} \mathbf{x}\) leading to the double integral

To separate the two integrals we define \(\vec{R}=\vec{x}-\vec{r}\) and the integral is rewritten as

In the first part of the integral we recognise the definition of \(f\left(\mathbf{q}^{2}\right)\) for a Coulomb potential as in equation (2.8) with \(z=-1\), while the second part of the integral is now the Fourier transform of the charge definition that we define as the form factor \(F\left(\mathbf{q}^{2}\right)\)

The cross-section of interaction between an electron and a charge with a spatial distribution \(\rho(\vec{x})\) can be obtained by substituting again into equation (2.7) with the form factor modifying the point-like cross-section as

In principle the measurement of the differential cross section can lead to a measurement of the form factor, and the inverse Fourier transform of the form factor can be used to measure the charge distribution. In practice, a functional behaviour of the charge distribution \(\rho(r)\) is assumed, and the parameters of the model are measured by fitting the prediction with experimental data.

In most case the charge distribution has a spherical symmetry, so the formula for \(F\left(\mathbf{q}^{2}\right)\) can be simplified to eliminate the integrals on the angular coordinates. In this case we write

Derivation

We start from equation (2.10)

And rewrite the integral in spherical coordinates as

The integral in \(d \phi\) is simply \(2\pi\) as there is no dependency on the azimuthal angle \(\phi\). While the integral in \(\theta\) can be done by changing variable to \(cos \theta\) and integrating in \(d \cos \theta\) between \(-1\) and \(1\)

Integrating in \(d \cos \theta\) we get

It is important to notice that for small momentum transfer \((q \approx 0)\) the nuclear substructure is not visible by the probe, and hence we expect the form factor to be 1 in this limit, so the cross-section is that of a point-like charge.

Example 2.3. Form factor of a solid sphere

Assume a nucleus of charge \(Ze\) has the charged distributed inside a solid sphere of radius \(a\)

Evaluate \(F\left(\mathbf{q}^{2}\right)\)

Solution

First we need to evaluate the constant \(C\) to ensure the distribution is normalised correctly, this is done by setting

Since the density is constant inside a sphere of radius \(a\), the integral will be simply the volume of a sphere of radius \(a\) multiplied by the constant \(C\)

so for \(r<a\) the density is

As the next step we evaluate the form factor using the formula in equation (2.12)

where the integral is zero for \(r>a\). If we change variable to \(z=\frac{q r}{\hbar}\) this gives

Substituting and defining \(b=\frac{q a}{\hbar}\)

which integrating by parts give

The graph for this distribution is shown in Fig. 2.5. The cross-section is proportional to the square of the form factor and will therefore exhibit a “oscillation” behaviour which is observed in real data (see for instance Fig 2.5 of [Martin]). By measuring this oscillation behaviour and identifying the points where the cross section is at a minimum we can measure the nuclear radius. (More discussion of this next semester in your nuclear physics course).

Fig. 2.5 Graph of the form factor for a uniform charge distribution inside a sphere or radius \(a\).#

For low momentum transfer interactions, it can be shown that

as expected. To give a physical interpretation we see that \(b \ll 1\) corresponds to

where \(\lambda\) is the De Broglie wavelength associated to the momentum transfer. That is to say that if the wavelength is larger than the nuclear size, the cross section observed is that of a point-like scatter centre.

Example 2.4. Point-like approximation for interaction with a \(^{48}Ca\) nucleus

A nucleus of \(^{48}Ca\) has a radius of approximately 4.4 fm and is treated as a solid sphere as in the example above. A beam of electrons of momentum \(p\) is scattered through the nucleus, estimate the maximum value of \(pc\) for which we can consider the interaction as point-like.

Solution

The interaction cross section corresponds to the point-like cross section if \(F(q^2)=1\), and we know that this is the case in the limit \(q\rightarrow 0\).

In the example above, we saw that this is the case for \(b\ll 1\). Looking at the graph, we can say that the approximation \(F(q^2)=1\) is valid to within a few percent for \(b<0.1\), so we take \(b=0.1\) as the maximum value for which the interaction can be treated as point-like.

Using the defintion of \(b\) we write

where we indicated the nuclear radius with \(R\). Hence

(Remember you can use \(\hbar c = 197\)MeV fm).

Earlier we saw that \(q\) depends on the beam momentum and on the scattering angle as

But since sine is always smaller than 1 we get

Which means that for electrons of momentum (and energy) above a few MeV we start observing a deviation from the point-like cross section formula and we are sensitive to the nuclear charge distribution.

In the next example we will see how the form factor distribution can be used to measure the nuclear radius.

Example 2.5. Measurement of the radius of the \(^{48}Ca\) nucleus

A beam of electrons of energy E=758 MeV is scattered through a nucleus of \(^{48}Ca\). The measurement of the differential cross section shows dips at the values \(\theta_1 = 17^\circ\), \(\theta_2 = 30^\circ\), and \(\theta^3 = 45^\circ\). Assuming that the \(^{48}Ca\) nucleus is spherical with a uniform charge distrubution, use the position of the dips to measure the nuclear radius.

(Note, the values of \(\theta_1\), \(\theta_2\) and \(\theta_3\) are taken from a figure on the textbook by Martin. )

Solution

The differential cross section is affected by the shape and size of the nucleus and the point-like cross section is modified as in equation (2.11)

From example 2.3 we know that

With

Hence we can evaluate

We make the assumption that the dips in cross section correspond to the zeros of the \(F(q^2)\) form factor, which can be evaluated numerically to be at \(b_1=4.49\), \(b_2=7.72\), \(b_3=10.90\). from which we can calculate the value of \(R\) for the three zeros.

\(b\) |

\(\sin \theta/2\) |

R (fm) |

|---|---|---|

4.49 |

0.148 |

3.94 |

7.72 |

0.259 |

3.88 |

10.90 |

0.383 |

3.70 |

Which is consistent with the measured radius of 4.4 fm, considering the approximation breaks down at the surface of the nucleus with a skin measured to be slightly smaller than 1 fm.

2.6. Summary of approximations made#

In deriving the form factor and the Coulomb interactions between an electron and a nucleus we made a few approximations, some were explicitly mentioned some were not. Removing each of the approximations will complicate the equations that we wrote. While this is possible, we will not pursue this here as it does not add to the understanding of the physics involved. The approximations are summarised as:

The scattering is elastic. Which means that the target and probe particle remain the same before and after the collision. This is like a game of snooker, assuming no energy is transferred to the balls in the form of heat (and that the balls do not crack!);

We used the “Born approximation”. This assumes that a single scattering occurs, and that the initial and final state electrons can be described by plane waves;

We neglected the spin of the particles. In the case of an electron scattering, the electron has spin \(\hbar / 2\) and the Rutherford cross-section needs to be modified to take into account additional final states due to the spins involved. This would lead to the Mott cross section formula, which is what is normally used in nuclear physics;

At higher energies, we can no longer neglect the recoil of the nucleus in the interaction. In practice, this can be done by replacing the value of \(q^{2}\) with the square of the four-momentum transfer. Although we will not prove it;

At higher energy the interaction with the magnetic moment of the nucleus can no longer be neglected.

2.7. Further reading#

Material for further reading can be found by accessing the textbooks from the “Resource List” in Blackboard. The material for this unit is taken from [Martin].

The definition and explanation of the concept of cross section can be found on [Perkins] section 2.10 and section 1.6 of [Martin]

A review of the Fermi golden rule and of the density of states can be found in Appendix A of [Martin]

A summary of the history of particle physics can be found on [Dodd]

A discussion on the nuclear shape and form factor is in [Martin] section 2.2 (But note the different definition of \(\rho\) )