5. Quantum Chromodynamics#

Learning objectives: Know the characteristics of the electromagnetic, strong and weak interactions.

In this unit we continue our study of the fundamental interactions of particle physics. We reuse the knowledge we acquired to describe QED to study the strong interactions between quarks and gluons. Quark and gluons carry a “colour” that can be seen as an equivalent of the electric charge in elecrodynamics. The interaction of particles with coulour goes under the name of Quantum ChromoDynamics or QCD in brief.

5.1. Strong interactions#

The strong interaction binds the constituents of nucleons and other hadrons. Its properties can be summarised as follows:

It acts only on quarks;

It is strong, overcoming the Coulomb repulsion in the nucleus;

It binds quarks in only two configurations: \(q q q\) for baryons (and \(\bar{q} \bar{q} \bar{q}\) for antibaryons) and \(q \bar{q}\) for mesons.

Note

The discovery of states known as “pentaquarks” was recently announced. These states are made of 4 quarks and one anti-quark, and they are very unstable. We will not consider these here, but for completeness we should point out their existence

In this section, we discuss the properties of the strong interaction, while we will cover the classification of hadrons in a later chapter.

The quarks in baryons can be described by a wavefunction which separates into a spin and a spatial part. However, it appears that the quarks violate the Pauli exclusion principle, in that there are cases where the total wave function is symmetric under the interchange of two identical quarks - indeed, in some cases three identical quarks have identical spin and orbital quantum numbers! For example the \(\Delta^{++}\)particle is made of 3 identical \(u\)-quarks and has a spin \(3 / 2\), which means that the quarks are all in the same quantum state, thus appears to violate the Pauli exclusion principle.

To explain this apparent contradiction we introduce an additional quantum number, which is different for all three quarks in a baryon. This quantum number also corresponds to the source or “charge” of the strong interaction. The fact that the sum of three equivalent but different “strong charges” are required to produce a neutral state has led to this charge being known as colour, in analogy with the addition of three primary colours, red, green and blue, making white light. Each quark is labelled as red, green or blue, and the combination of three quarks of different colour make a colour neutral object, e.g. a baryon.

Antiquarks carry the equivalent “anticolours”, and the combination of a quark with a colour (e.g. red) with an antiquark with the corresponding anticolour (e.g. anti-red) also forms a colour neutral object, which we call a meson.

All the particles observed in nature are colour neutral and quarks can not be observed independently. We will see the reason for this later in this section, for now it is important to stress that all the observed particles are combinations of 3 quarks (baryons), of 3 antiquarks (antibaryons) or a quark-antiquark pair (mesons).

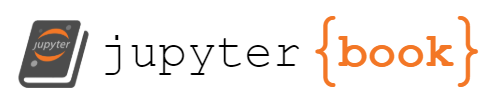

The strong interaction is a gauge interaction mediated by a massless, spin 1 gluon, \(g\), which is electrically neutral but carries both a colour and an anti-colour such as red- antiblue. The coupling constant is known as \(\alpha_{S}\) (alpha-strong) and the theory is known as Quantum Chromodynamics or QCD in analogy with QED. Fig. 5.1(a) shows the interaction between two quarks of different colour (red and blue in this example) by exchanging a gluon carrying red-antiblue. Unlike in QED, the gluon e.g. the exchange quantum is also a source of the field as it carries colour, so processes such as the branching of one gluon into two can occur, with the vertex in Fig. 5.1(b) also possible along with the vertex in Fig. 5.1(c) which is similar to the basic QED vertex.

Fig. 5.1 Example Feynman diagrams for the QCD interactions.#

A consequence of the additional gluon interaction vertex is a different expression for the static QCD potential as a function of the distance to the source \((r)\), which takes the form:

The first term is similar to the QED potential

Note how the \(\alpha_{S}\) constant in the QCD expression replaces the \(\alpha_{e m}\) constant in QED.

The second term has an interesting dependency on \(r\), which means that the potential energy gets larger as the distance increases. In QED the potential energy goes to zero for large distances, which means that the potential vanishes as we move away from the source. In QCD if a quark-antiquark pair is pulled apart their potential energy will increase linearly with the distance.

The behaviour of a quark-antiquark pair is shown in Fig. 5.2 (which is not a Feynman diagram, but just a drawing of how a quark-antiquark pair behaves). As the distance increases from picture (1) to picture (2), the potential energy increases. If we keep pulling, there is enough potential energy to create a new quark-antiquark pair as in picture (3). Hence quarks cannot be isolated and studied individually, unlike electromagnetic charged particles. This property is called quark confinement, and is a specific feature of QCD derived by the presence of additional interaction vertexes as the one in Fig. 5.1(b).

Fig. 5.2 Picture of a \(q \bar{q}\) pair being pulled apart until a new pair is created..#

If a quark is ejected from a hadron, the colour field builds up until it becomes energetically favourable to create a quark-antiquark pair and reduce the field. The new \(q\) and \(\bar{q}\) are attracted to the original particles, and produce a colourless meson and baryon. When many pairs are produced, this results in a jet of particles following the original quark direction. These can be observed both in inelastic scattering of a lepton from a hadron (where the struck quark in the hadron is ejected) and in \(e^{+} e^{-}\)annihilation, where a rapidly separating \(q \bar{q}\) pair is produced. The strong interaction is sometimes described as being a short-range force. However, being mediated by massless bosons, the strong force between quarks is not short-ranged. The strong force between hadrons which are colourless overall - e.g. the force between nucleons in the nucleus - does appear to be short-ranged, in exactly the same way that the electromagnetic force between electrically neutral molecules in a crystal appears short-ranged.

Example 5.1. Interaction strength of the strong force.

Evaluate the magnitude of the two terms of the potential between two quarks separated by 1 fm . Use the experimental values \(k=0.85\ \mathrm{GeV}\, \mathrm{fm}^{-1}\) and \(\alpha=0.2\).

Solution

The first term is

The second term is

The magnitude of the electrostatic potential at the same distance is

This shows that at a distance of 1 fm , which is of the order of a nuclear radius size, the potential energy is dominated by the \(k r\) term of the strong force.

5.2. Electron-positron annihilation#

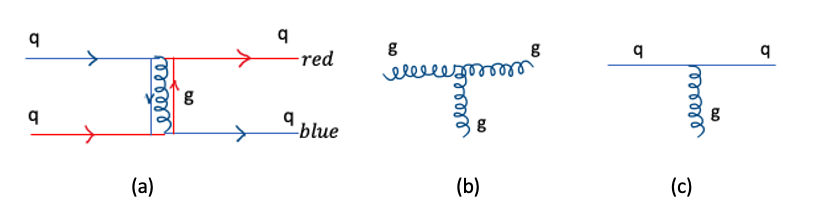

Electron-positron annihilations produce a particle-antiparticle pair through a timelike virtual photon. The interaction is governed by the rules of QED and the process

is described by the Feynman diagram in Fig. 5.3 (left). A similar interaction can produce a quark-antiquark pair as in Fig. 5.3. The two diagrams are identical, the only difference is that the charge of the particles on the left side of the Feynman diagrams.

Fig. 5.3 Feynman diagrams for the QED \(e^{+} e^{-} \rightarrow \mu^{+} \mu^{-}\)process (left) and the QED \(e^{+} e^{-} \rightarrow q \bar{q}\) process (right)#

In the case of the muon pair production the amplitude of the interaction is proportional to the product of the charges of the electron-positron pair (left) and that of the muon-antimuon pair (right), e.g. \(e^{2}\), and the cross section is proportional to the square of the amplitude,

In the case of the production of a quark-antiquark pair, the amplitude is proportional to the product of the charge on an electron, \(e\), and the charge on the quark, say \(z e\). The cross-section is thus proportional to

The quarks are not observed themselves, but seen in the combinations known as hadrons. The ratio, \(R\), of the cross-section for production of hadrons divided by that for the production of \(\mu^{+} \mu^{-}\)pairs at the same energy is thus given by

where the sum is over all quarks which can take part in the production of hadrons. The type of quarks that can be produced depends on the energy of the interaction, since quarks have different masses. The masses of the \(u, d, s\) quarks is below 100

MeV , while the mass of the \(c\)-quark is about 1.5 GeV and that of the \(b\)-quark about 5 GeV .

If the centre-of-mass energy is below twice the mass of the charm quark (e.g. \(E<3 \mathrm{GeV}\) ), only \(u \bar{u}, d \bar{d}, s \bar{s}\) pairs can be produced;

If the centre-of-mass energy is \(3 \mathrm{GeV}<E<10 \mathrm{GeV} u \bar{u}, d \bar{d}, s \bar{s}\) and \(c \bar{c}\) pairs can be produced;

If the centre-of-mass energy is \(E>10 \mathrm{GeV} u \bar{u}, d \bar{d}, s \bar{s}, c \bar{c}\) and \(b \bar{b}\) pairs can be produced.

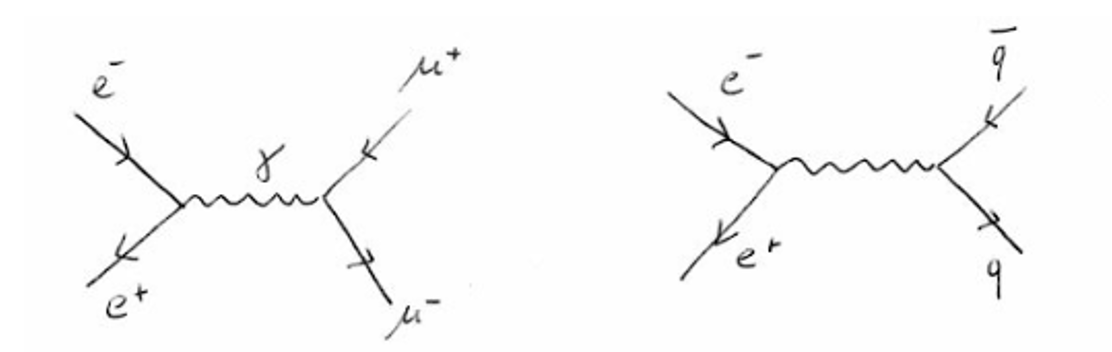

Note that since each quark can exist in 3 colours, the sum must be over both colours and flavours. At low energies, where \(u, d\) and \(s\) quarks can be produced, the value of \(R\) is then predicted to be

As the \(c\) and \(b\) thresholds are crossed, the value of \(R\) goes through wide excursions in resonance regions before settling down to values expected to be \(10 / 3\) and \(11 / 3\). Fig. 5.4 shows the experimental measurement of the ratio \(R\) as a function of the centre-of-mass energy. The additional factor of 3 in front of the expression of \(R\) is evidence that in reality three type of quarks exist with different colours as predicted by the QCD theory.

Fig. 5.4 The ratio \(R\) between the cross-section for \(e^{+} e^{-} \rightarrow\) hadrons, and the cross=section for \(e^{+} e^{-} \rightarrow \mu^{+} \mu^{-}\)for values of the centre of mass energy below 40 GeV . The fact that \(R\) is constant above 10 GeV centre of mass energy is proof of the point-like nature of hadron constituents. The data come from many storage-ring experiments.#

5.3. Hadron jets and the discovery of the gluon#

The emergence of jets of hadrons is observed in collider experiments, and is a way quarks and gluons in the final state can be identified by experiments such as those at the Large Hadron Collider. Quarks are emitted as the result of a high-energy interaction and show themselves as “jets” of particles. Adding the energy and momentum of the particles in a jet can lead to the measurement of the energymomentum of the original quark producing it. Particles are clustered in a cone around an axis, which is assumed to be the original direction of the quark.

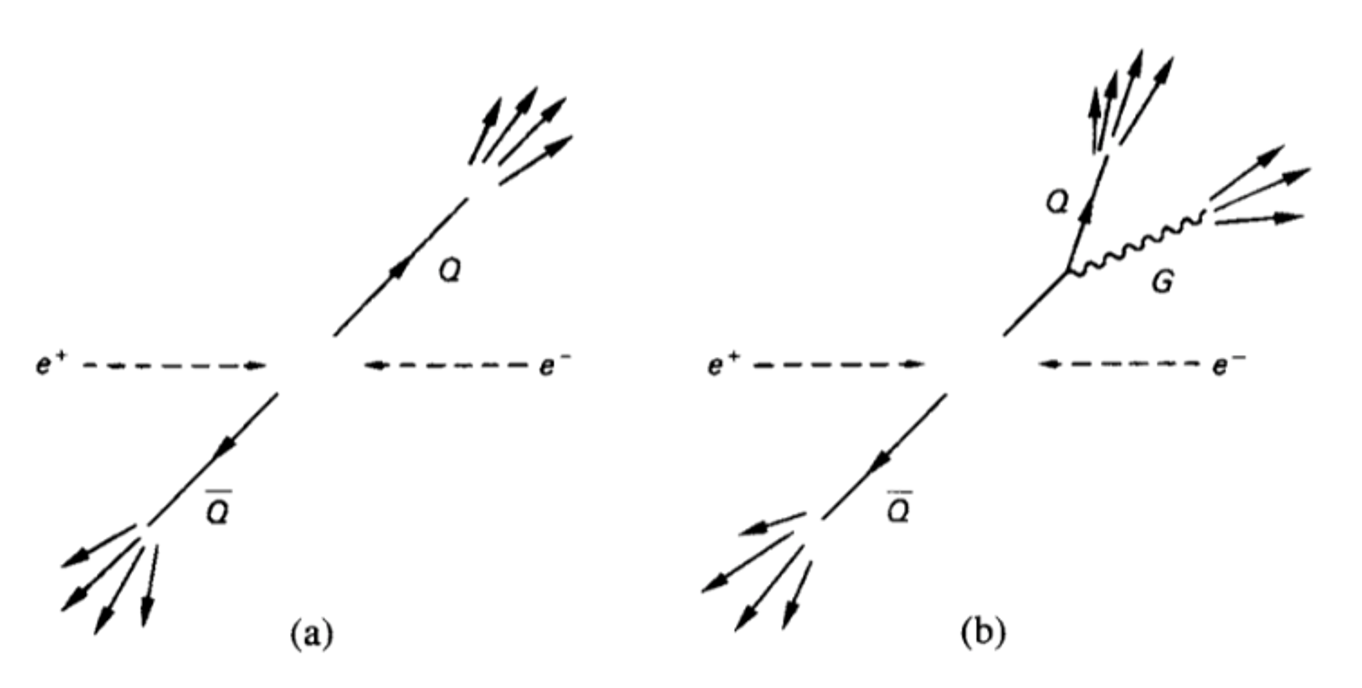

Similarly, gluons can also be emitted as a result of a scattering and since they also carry colour they are observed as jets of particles. This is shown as a diagram in Fig. 5.5

Fig. 5.5 Diagram showing the hadronisation of quarks and gluons into jets. Illustration of the \(e^{+} e^{-} \rightarrow \bar{q} q\) (left) and the \(e^{+} e^{-} \rightarrow \bar{q} q g\) interaction (right). These are not Feynman diagrams#

Example 5.2. Feynman diagrams for quarks and gluons production

Draw a Feynman diagram for the \(e^{+} e^{-} \rightarrow \bar{q} q g\) interaction. Explain to which power of \(\alpha_{\mathrm{em}}\) and \(\alpha_{\mathrm{s}}\) the cross section is proportional to.

Solution

The Feynman diagram is the same as the one in Fig. 5.3 (right), where we added a gluon to one of the quark legs in the final state

Fig. 5.6 Feynman diagram for the production of two quarks and a gluon in electron positron collisions.#

Since there are two electromagnetic vertexes and one QCD vertex, the cross section will be proportional to \(\alpha_{em}^2 \alpha_S\)

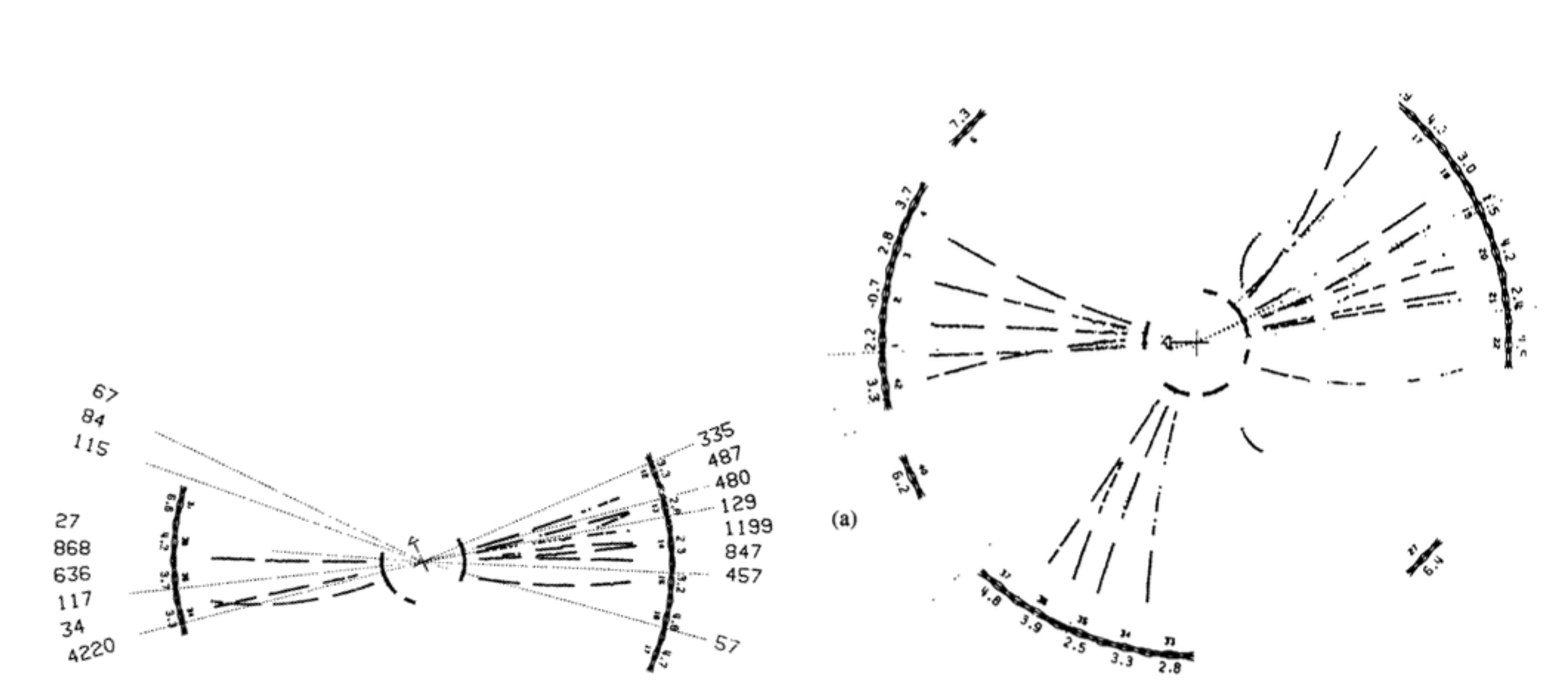

Some of the initial results on hadron jets are presented in [Perkins], and refer to the study of \(e^{+} e^{-} \rightarrow \bar{q} q\) at a centre of mass energy of 30 GeV (figure 16 left, from Perkins Fig 6.8a). In a fraction of the collisions events with three jets were observed compatible with the observation of the \(e^{+} e^{-} \rightarrow \bar{q} q g\) interaction and the emission of a gluon in the final state (figure 16 right, see Perkins Fig 6.8b). The experimental results show the particles emerging from the vertex on a plane perpendicular to the direction of travel of the electron-positron pair. In the events shown, two or three clear clusters of hadron jets are visible. The observation of the angular correlations in events with three jets is compared with theoretical models where the gluon has spin-0 and spin-1 (Perkins Fig 6.9b), with the result that the gluon is a particle with spin 1.

Fig. 5.7 Experimental results for the \(e^{+} e^{-} \rightarrow \bar{q} q\) interaction (left) and the \(e^{+} e^{-} \rightarrow \bar{q} q g\) (right). The lines represent particles emerging from the interaction in a cross-section view of an experimental detector#

5.4. Deep inelastic scattering#

The values of \(R\) above indicate that hadrons are indeed made of fractionally charged, coloured objects. We now look for evidence that hadrons are made of point-like particles, e.g. the quarks.

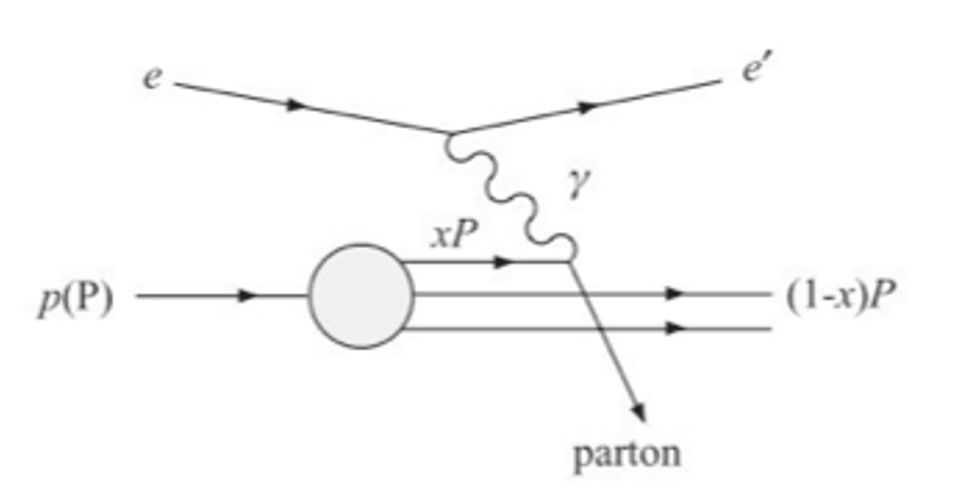

To study this, we scatter electrons off nucleons via the exchange of a virtual photon, at high enough energy we will be probing the structure of the proton and the neutron, which absorbs energy and breaks up to form a hadronic system. Scattering in this high-energy regime goes under the name of “deep inelastic scattering” and was awarded the Physics Nobel prize in 1990.

From an experimental point of view, the deep inelastic scattering is an extension of the elastic scattering we studied in Unit 2 to measure the charge distribution of nuclei. The main difference is that the energy of the electrons, used as probes, is greatly increased to 10 GeV or more. Because of that, we need to introduce a new notation which considers the fact that the fact that the nucleons break up and absorb some of the initial energy (hence the process is inelastic) and that the kinematics of the particles involved need to be treated using special relativity.

Figure 17 shows a drawing of a deep inelastic scattering collision between an electron and a proton, with the proton breaking up into a hadron system. We indicate with \(W\) the invariant mass of the hadron system calculated using the Lorentz invariant expression

Where \(E_{j}\) and \(\vec{p}_{j}\) are the energy and momenta of the hadrons produced in the collision.

Fig. 5.8 Diagram of a deep inelastic scattering interaction between an electron and a proton.#

In the case of the elastic scattering we used the quantity \(q^{2}\) to indicate the change of the electron momentum in the collision. Since this quantity is not Lorentz invariant it is not suitable as a variable to describe a relativistic collision. Instead we define the quantity that is related to the change of energy and momentum of the electron

where \(E_{i}\) and \(E_{f}\) are the initial and final lepton energies, \(\vec{p}_{i}\) and \(\vec{p}_{f}\) are the initial and final momentum of the electron. In case of an elastic scattering where \(E_{i}=E_{f}\) as in Unit 2, we obtain once again the momentum transfer \(q^{2}\). Once again we indicate with \(\theta\) the lepton scattering angle and, assuming the mass of the electron is negligible, it can be easily shown that

Hence the quantity \(Q^{2}\) is related to the “transfer” of energy-momentum between the initial and final state photon, while \(W\) is related to the hadronic final state.

We now define a variable \(\nu\) as

where \(M\) is the mass of the nucleon that is scattered on. Since this is a combination of Lorentz invariant quantities, the variable \(\nu\) is also a Lorentz invariant quantity. To understand the physics meaning of the variable \(\nu\), we can evaluate it in the proton rest-mass frame as

The derivation of \(Q^{2}\) and \(\nu\) are done as part of Exercise B, along with a more mathematical description of the deep-inelastic scattering.

Elastic scattering limit In the case of an elastic scattering the nucleus remain unchanged, which means

Therefore the ratio

indicates if the scattering is elastic or not. \(Q\) and \(\nu\) are not independent in the case of elastic scattering, but are said to “scale”, and the variable \(x\) defines the degree by which the scattering is inelastic, with \(x=1\) for elastic scattering and \(x<1\) for inelastic scattering.

Scattering off quarks Now if we consider the nucleon to be made up of stationary point-like particles of mass \(m_{q}\), then \(x\) will be a constant for elastic scattering off these particles, which will fix

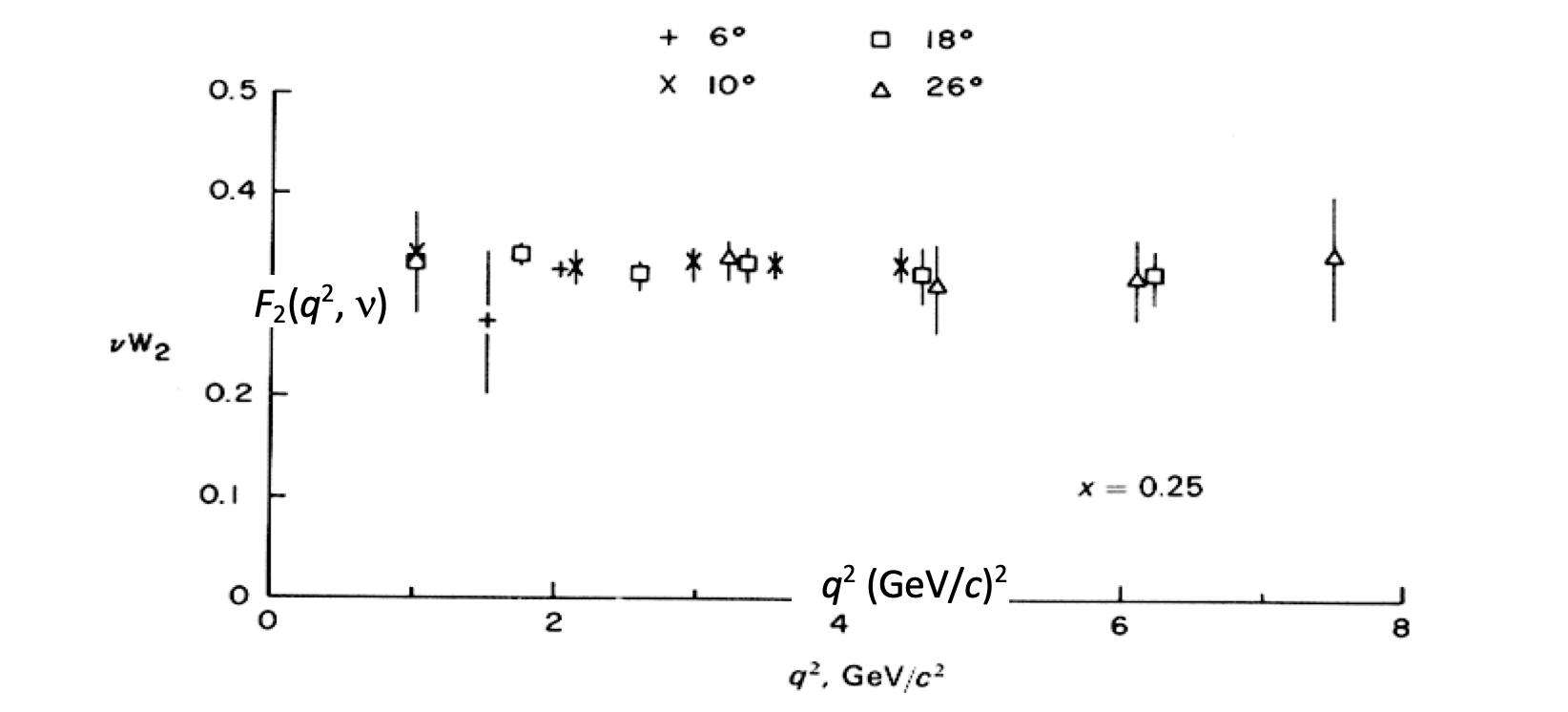

However, unlike the nucleon, the quark will not be at rest, having considerable momentum within the proton. When we perform a Lorentz transform from the rest frame of a quark to that of the proton, integrating over the distribution of quark momenta leads to the form factor of the proton. However, as long as the quarks are point-like the form factor should only depend on \(Q^{2}\) through the dimensionless ratio \(x\), and the cross section shows “scale invariance”. This is indeed observed, as shown in Fig. 5.9. (Here \(F_{2}\) is proportional to the form factor).

Fig. 5.9 \(F_{2}\) as a function of \(q^{2}\) at \(x=0.25\). For this choice of \(x\), there is practically no dependence on \(Q^{2}\), that is, there is exact “scale invariance”. (Data from the Stanford Linear Accelerator Center.).#

Scattering from an extended object like the proton (rather than from point-like constituents within it) would produce a very different distribution. As calculated in an early homework, the form factor for a structure-less proton drops rapidly with \(Q^{2}\), reaching very small values for \(Q^{2}\) above 1 to \(2 \mathrm{GeV} / \mathrm{c}^{2}\).

5.5. Renormalisation and running coupling constants#

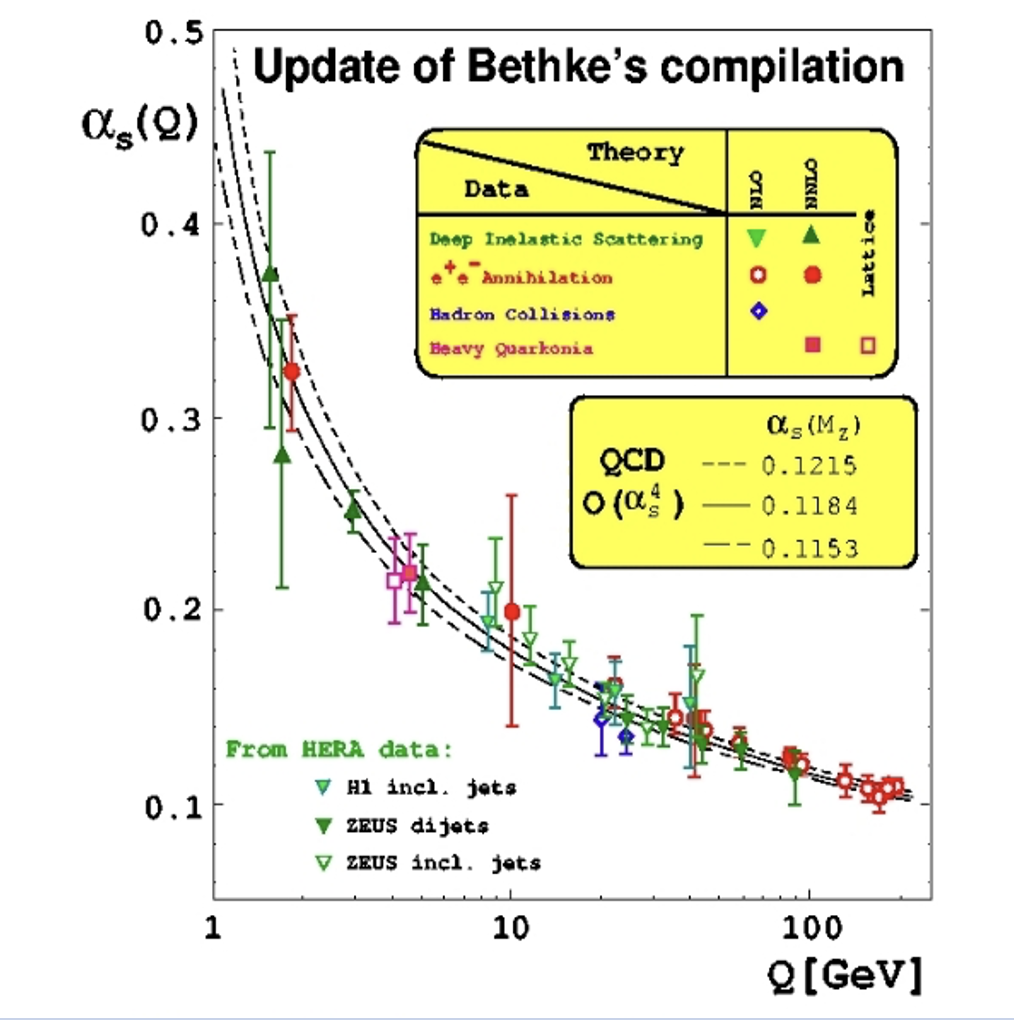

We saw earlier in section 4 that loops in Feynman diagrams lead to a change of the interaction process. We described such loops in QED, but similar diagrams are possible also in QCD with loops of gluons and quarks. The consequence is that infinite number of loops can be added to particle can have self-interaction terms and adding up the contributions from this virtual particle interactions can lead to divergent terms. To avoid this divergence, theories are “renormalised” to remove these infinite terms. This may sound like a gimmick, but It is a commonly used techniques in particle physics. This means that at a distance particles can be observed regardless of a cloud of virtual particles that surround them and make precise predictions. This is called “renormalisation” and was at the centre of the 1999 Nobel prize for Physics. As we get closer to a particle, the interaction with the virtual cloud of particle surrounding it is reduced, which means the strength of interaction increases. For instance the electromagnetic coupling constant has a value \(\alpha_{\mathrm{em}}=1 / 137\) at the atomic scale of interaction (e.g. a few eV ). The value of \(\alpha_{\mathrm{em}}\) increases with the increase of the energy scale to a value of \(1 / 128\) where the interaction quantum has a total energy of \(\approx 90 \mathrm{GeV}\). 90 GeV is the mass of the Z boson and corresponds to an energy that was used to study weak interactions at the LEP collider. A change in \(\alpha_{\mathrm{em}}\) would not make an appreciable difference in atomic physics, but it is important in particle physics. A similar behaviour is observed in QCD, with a much larger change in the strong interaction coupling constant \(\alpha_{S}\) that is shown in Fig. 5.10. Therefore we call \(\alpha\) a “running coupling constant”, which is not a constant after all!

Fig. 5.10 The change in \(\alpha_{S}\) as a function of momentum transfer. (Note the \(\log\) scale.)#

5.6. Further reading#

There is much more on QCD that we could cover in these lectures, if you want to know more:

Colour and QCD material is taken from chapters 5.1 and 5.2 of [Martin]

The study of jet hadrons is taken from [Perkins] section 6.4 and [Martin] section 5.6

The discussion on QCD can be found in [Perkins] section 2.5 and [Martin] section 5.4

The counting of colours and the ratio R can be found in [Martin] section 5.7

The Deep Inelastic Scattering is discussed in [Martin] section 5.8

Running coupling constants and renormalisation can be found in [Perkins] section 6.5

Nobel prize for the deep inelastic scattering https://www.nobelprize.org/prizes/physics/1990/9589-the-deep-inelastic-collision/

Normalisation and 1999 Nobel prize https://www.nobelprize.org/prizes/physics/1999/press-release/

5.7. Addendum: The colour of gluons#

We discussed in the lectures that there is an octet of coloured gluons. Here we will show why there are 8 such states. Remember that there are 3 colours, which we label \(r, g\) and \(b\) (and 3 corresponding anticolours \(\bar{r}, \bar{g}, \bar{b}\) ). Steps are enumerated in logical order

Each gluon carries a colour and an anticolour. This means there are 9 orthogonal colour-anticolour states:

The first six of these composites are explicitly coloured, and we label them as \(G_{1}\) to \(G_{6}\). (To avoid confusion with “green”, we will use capital \(G\) to represent gluons).

The other three states \(G_{7}, G_{8}\) and \(G_{0}\) will have no “explicit” colour. Since \(G_{0}\) to \(G_{8}\) are quantum states, we want to represent them using an orthogonal set.

To define the property of the “neutral” states, we should consider the colour swap operations, e.g. an operator that changes \(r \leftrightarrow g\) and \(\bar{r} \leftrightarrow \bar{g}\). With this operator we would swap the states \(G_{1}\) and \(G_{3}\)

The state

does not change under any colour swap operation. (Note the normalisation is chosen to normalise \(\left|G_{0}\right|^{2}=1\) ). We call this the colour singlet state, as it is decoupled from the other states.

We define two more states that are orthogonal to the 7 states defined so far. This is one possibility as there will be more possible states that satisfy this requirement:

If we apply a colour swap combination to the \(G_{7}\) and \(G_{8}\) states, we end up with a linear combination of the two states, for instance try to apply the \(g \leftrightarrow r\) operator to \(G_{7}\)

The 9 gluon states are divided into an “octet” which is a set of states that transform into each other via the colour swap operations, and a “singlet” that is a state that is invariant under the colour swap combination. A proper application of group theory shows that all of \(G_{1}\) to \(G_{8}\) have the same coupling in quark strong interactions, and correspond to the octet of physical gluons. \(G_{0}\) is a singlet with no coupling and therefore does not correspond to a gluon. We will revisit the concept of singlet and octet at the end of the course when discussing quark bound states.