6. Weak interactions and invariance principles#

Learning objectives:

Know the characteristics of the electromagnetic, strong and weak interactions.

be able to use Feynman diagrams to describe interactions;

In this unit we complete our overview of fundamental interactions and we cover the weak interactions. Weak interactions are needed to explain nuclear decays, and are mediated by heavy spin-1 boson that can be either neutral \(Z^0\) or charged \(W^\pm\). We will introduce the parity and charge conjugation quantum numbers and show that weak interactions violate them and the consequence of it.

6.1. Characteristics of weak interactions#

In the previous sections we talked about interactions that are mediated by photons (QED) and gluons (QCD). In terms of relative strength we said that strong interactions are “stronger” than electromagnetic ones. In the same spirit we introduce weak interaction which, as the word says, have a weaker relative strength than the electromagnetic ones. Weak interactions are responsible for radioactive beta decays in nuclear physics, as well as many other phenomena in particle physics, which are the subject of this unit.

As previously mentioned, weak interactions are mediated by massive bosons, the \(W^{ \pm}\)and the \(Z^{0}\) with a mass of approximately \(80\, \mathrm{GeV}\ / \mathrm{c}^{2}\) and \(91\, \mathrm{GeV} / \mathrm{c}^{2}\), respectively. All fermions in the standard model interact via the exchange of weak bosons, this includes the leptons (both charged and neutrinos) and the quarks. Therefore neutrinos can only interact via weak interactions, which makes very difficult to detect, as their interaction cross section is very small.

There are two types of weak interactions, based on the boson being exchanged

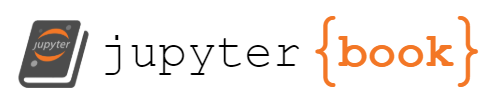

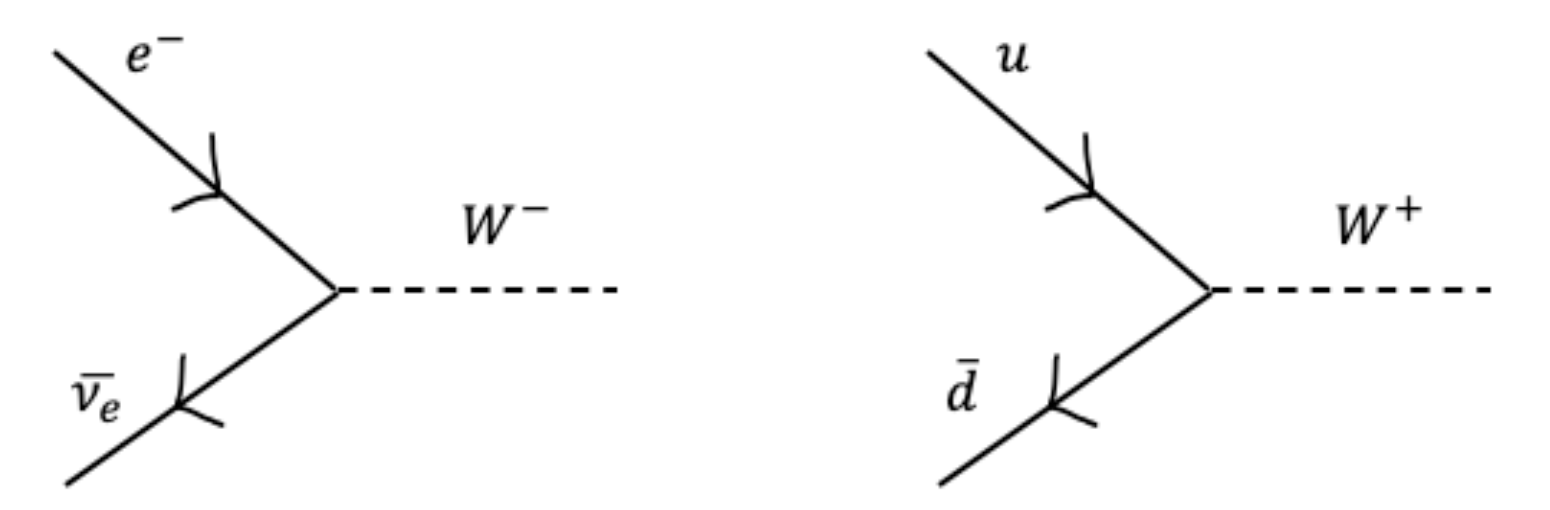

Charged-current interactions are mediated by the exchange of \(W^{ \pm}\)bosons with diagrams like the one in Fig. 6.1. Interactions between different lepton family are forbidden, while interactions between different quark families are allowed. Hence the conservation of the 3 lepton numbers and one baryon number. Charged-current interactions are responsible for the nuclear \(\beta\)-decays, and the muon decay, see Fig. 6.2 (a), and for neutrino interactions, see Fig. 6.2 (b)

Neutral current interactions are mediated by the exchange of \(Z^{0}\) bosons and interactions are with leptons or quarks of the same type (or flavour).

Fig. 6.1 Weak interactions vertexes mediated by the W boson coupling leptons (left) and quarks (right)#

Fig. 6.2 (a) Neutrino-neutron interactions mediated by the charged current. (b) Muon decay. From Perkins fig 2.6.#

6.2. Comparing interaction types#

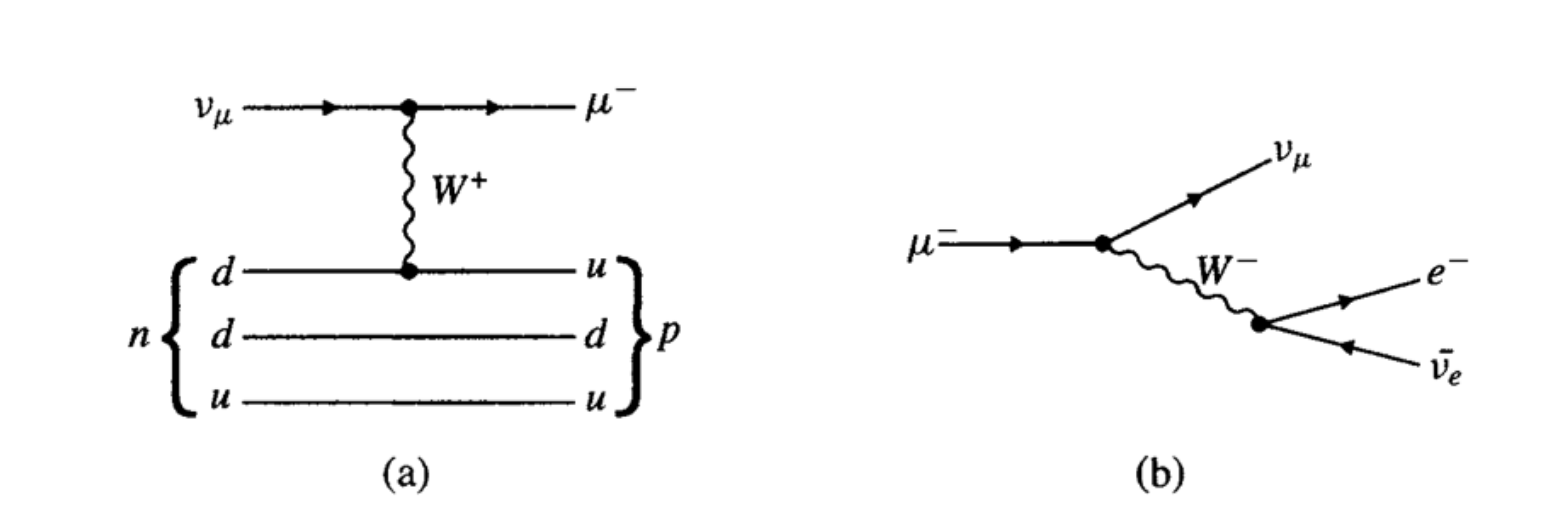

Now that we introduced the three fundamental interactions in particle physics, we can compare them and review how we evaluate their Feynman diagrams to study physical processes. Figure 6.3 shows Feynman diagrams comparing simple \(2 \rightarrow 2\) processes mediated by electromagnetism, strong and weak forces.

Fig. 6.3 Three fundamental interactions compared. Electromagnetic interaction \(e^+e^- \rightarrow \mu^+ \mu^-\) (left), strong interaction \(u\bar{u} \rightarrow d\bar{d}\) (middle), and weak interaction \(e^- \bar{\nu}_e \rightarrow \mu \bar{\nu}_\mu\) (right).#

In Unit 2 we discussed the Fermi golden rule and we said that the rate of a process is proportional to the square of the matrix element. We defined the matrix element as the Fourier transform of the potential and described it using a Feynman diagram. The matrix element is proportional to

The product of the “charges” at the vertexes. In the case of electromagnetism, that is the electric charge, or the constants \(g_{s}, g_{w}\) in the case of the strong and weak interactions, respectively

The distance \(1 / \mathrm{r}\) in the case of massless boson mediating the force or \(\frac{1}{r} e^{-r / R}\), where the range R is related to the mass of the mediator \(R=\hbar / m c\) as shown in Exercise A .

We express the interaction rates in terms of proportionality to the factors above, so we have

For the electromagnetic interaction, the potential is proportional to

therefore the matrix element is proportional to its Fourier transform, which we calculated as

and the rate is proportional to

Which we showed leads to an expression for the Rutherford cross section and its dependency on \(\sin ^{2} \theta / 2\).

Likewise for the strong interaction at short distances (《1 fm ), we can evaluate a rate of interaction that depends on the strong constant \(\alpha_{S}\)

For weak interactions, the same argument still applies, except that when we calculate the Fourier transform of the potential expression, we need to use the formula for the Yukawa coupling and therefore

For interactions where the momentum transfer (q) is smaller than the mass of the mediator, e.g. when the interaction is at a scale of a few GeV or smaller, we can neglect the value of \(q\) at the denominator and the expression for the rate is given by

6.3. Particle decays#

The decay of particles is also described by Feynman diagrams in a way that is similar to the treatment we used to study the cross section of particle interaction. For particle decays we apply once again the Fermi golden rule and their rate of decay is proportional to the square of the matrix element. Therefore we expect larger rate of decays, when particle decay via the strong interaction, with lower rates for the electromagnetic interaction, and even lower when weak interactions mediate the decay.

In the case of weak decays, which are observed also in nuclear physics, the original Fermi theory of beta decay involved a point like “contact interaction” with a coupling constant

This value of \(G\) is compatible with all the observed decay rates for the muon decay and other nuclear decay processes, and is independent on the energy allowed in the decay.

The effective strength of the weak interaction at low energies thus depends both on the coupling of the W to fermions, \(g\), and upon its mass. At low energies, the constant \(G\) is proportional to

so if \(m_{w}\) is large, the weak coupling \(g\) is not necessarily very small. In fact we will see that the weak and electromagnetic theories are “unified” as a single theory which goes under the name of electroweak theory, with the consequence that \(g_{W} \approx e\). The so-called weakness of the weak interactions is due to the presence of the mass term in the propagator that causes the behaviour we observe at the GeV energy scale.

Example 6.1. Pions lifetime

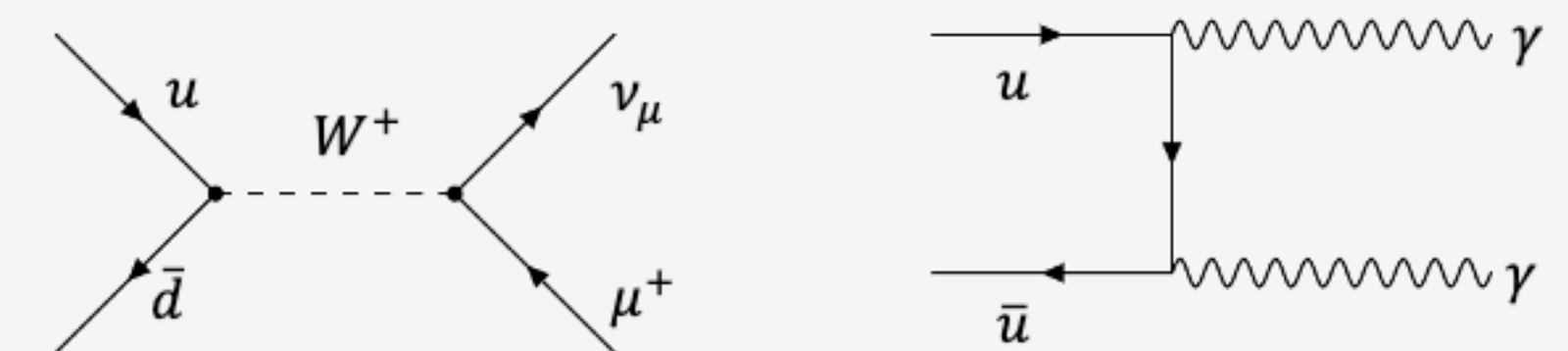

The lifetime of the \(\pi^{+}\)(bound \(u \bar{d}\) state) is \(2.6 \times 10^{-8} \mathrm{~s}\), while the lifetime of the \(\pi^{0}\) (bound \(\bar{u} u\) state) is \(8.4 \times 10^{-17}\) s. Sketch the Feynman diagrams for the decay of these two particles and show that the \(\pi^{+}\)decays via a weak interaction, while the \(\pi^{0}\) decays via an electromagnetic interaction.

Solution:

The Feynman diagrams for the two decays are sketched below

Fig. 6.4 Pion decay diagrams#

The \(\pi^{+} \rightarrow \mu^{+} v_{\mu}\) decay is mediated by a weak interaction, while the \(\pi^{0} \rightarrow \gamma \gamma\) is mediated by the electromagnetic interaction. As a consequence the lifetime of the charged pion will be proportional to \(\alpha_{W}^{2}\), and the lifetime of the neutral pion is proportional to \(\alpha_{e m}^{2}\). Therefore the lifetime of the charged pion is much longer than that of the neutral pion.

6.4. Experimental results on weak interactions#

The weak interaction responsible for beta decay involves a charged (or charge-changing) current, and the W must exist as \(\mathrm{W}^{+}\)and \(\mathrm{W}^{-}\). This suggested there might also be a weak neutral current, propagated by a third boson, the \(Z^{0}\). Evidence for this was first observed at CERN in 1973 in the form of neutrino interactions \(v_{\mu} N \rightarrow v_{\mu} X\) (where \(N\) is a nucleus and \(X\) a hadronic system) and \(v_{\mu} \mathrm{e} \rightarrow v_{\mu} \mathrm{e}\). However, this exposed a new theoretical problem. At sufficiently high energy, it should be possible to produce real \(\mathrm{W}^{+} \mathrm{W}^{-}\)pairs in \(\mathrm{e}^{+} \mathrm{e}^{-}\)annihilation through the \(\mathrm{Z}^{0}\), and a calculation shows that at very high energies this cross section again becomes unphysically large. The diagram for this process would be cancelled by that corresponding to electromagnetic annihilation to \(\mathrm{W}^{+} \mathrm{W}^{-}\)through a photon, but this cancellation will only occur if the weak coupling constant \(g\) is equal to the electromagnetic coupling, \(\sqrt{ } \alpha\). (Note that at such very high energies, the mass of the \(Z^{0}\) becomes insignificant.) Although this argument was originally a theoretical one, experimental evidence from \(\mathrm{W}^{+} \mathrm{W}^{-}\) production at the large electron-positron collider, LEP, many years later confirmed this prediction, and such results will be presented in the lectures.

In the 1960’s, Glashow, Salam and Weinberg proposed the unification of the electromagnetic and weak interactions as a single gauge theory with a common coupling constant. This implied that the mass of the W and Z must be about \(90 \mathrm{GeV} / \mathrm{c}^{2}\). (At low energies, the W and Z cannot be produced as real particles, and the electromagnetic and weak interactions appear as separate processes.) The first real weak bosons were produced at the CERN antiproton-proton collider, which effectively allowed antiquarks and quarks to interact. In 1982, processes such as

were observed in the UA1 and UA2 experiments, while the next year the rarer but cleaner signature

was observed.

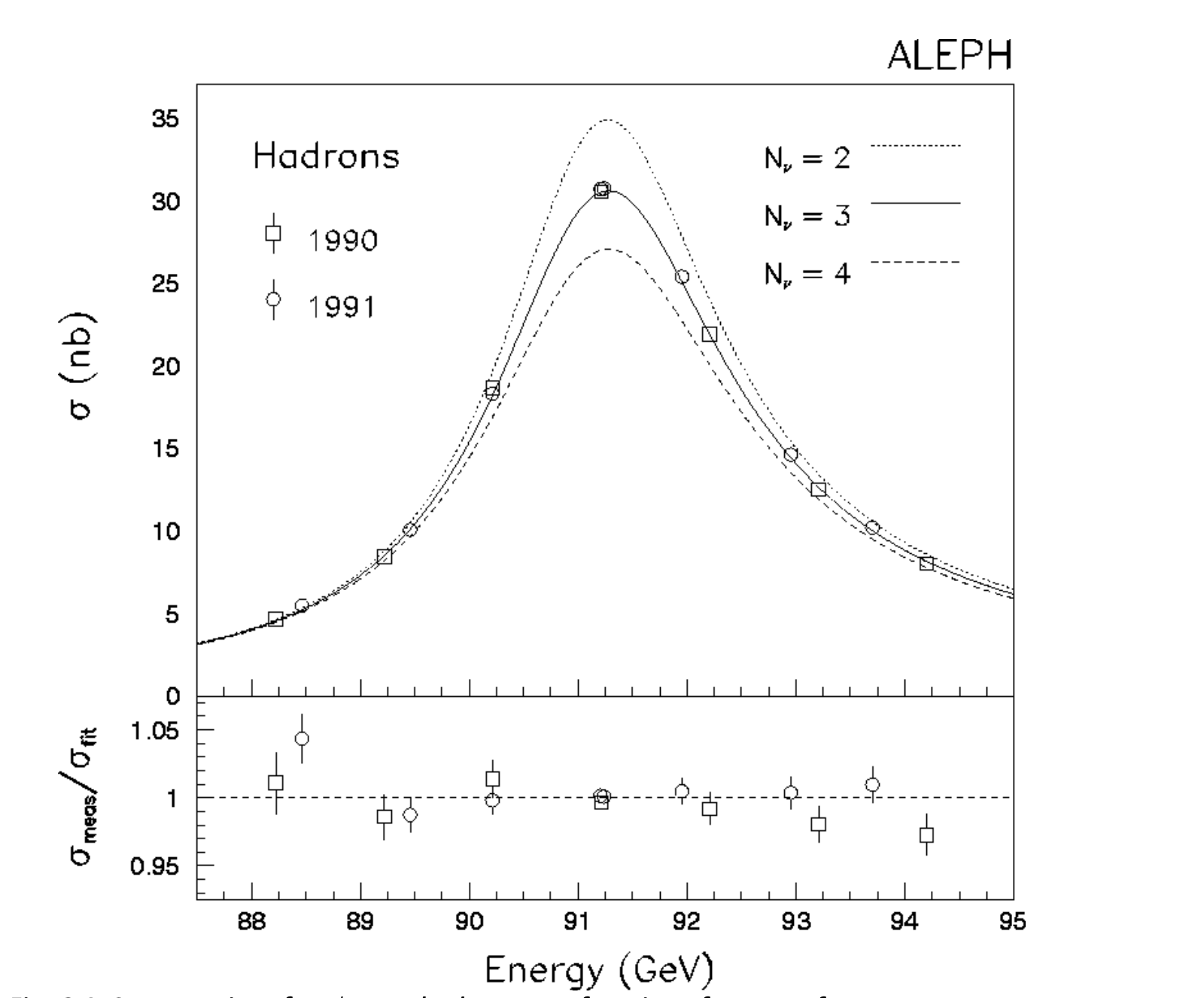

In the late 1980s, a large \(\mathrm{e}^{+} \mathrm{e}^{-}\)collider, LEP, was built at CERN, allowing the “mass production” of \(Z^{0}\) bosons. By colliding the particles with exactly the right energy to supply the \(Z\) mass, a large resonance in the cross section occurs, and now several million \(Z^{0}\) decays have been observed, shared between the 4 large experiments. Subsequently, the Large Hadron Collider, is now observing billion of events where \(W\) and \(Z\) bosons are produced, leading to the measurement of their masses with a precision of 12 MeV and 2 MeV respectively.

The \(Z\) couples to all fermion-antifermion pairs, including neutral neutrinos. The decays to neutrinos are basically undetectable, as neutrinos leave no tracks and can pass through large amounts of material without interacting, but nonetheless they modify the properties of the \(Z\). Results on neutrino production were some of the most important to emerge in the early days of LEP!

The \(Z\) is a very short-lived particle, with a lifetime of only \(2.6 \times 10^{-25} \mathrm{~s}\). The uncertainty principle implies a relationship between the uncertainty in energy (and hence mass) and that in time. Thus, in \(\mathrm{e}^{+} \mathrm{e}^{-}\)annihilation, the \(\mathrm{Z}^{0}\) is seen with a width in mass of about 2.5 GeV (FWHM), as shown in Fig. 6.5 Decays of the \(Z\) into neutrinos have two effects. Each species of neutrino decreases the number of visible \(Z\) decays by \(13 \%\) and also shortens the lifetime, and hence increases the width by 0.176 GeV . Measurements by the ALEPH collaboration at LEP show that the data imply \(N_{v}=2.994 \pm 0.012\) i.e. 3 ! There are therefore no new generations of lepton and neutrino (unless the mass of the new neutrino is greater than \(45 \mathrm{GeV} / \mathrm{c}^{2}\) - very different from the three known species, which are almost massless).

Fig. 6.5 Cross sections for \(e^{+} e^{-} \rightarrow\) hadrons as a function of centre-of-mass energy. The Standard Model predictions for \(N_{v}=2,3\) and 4 are shown.#

6.5. Symmetries and invariance principles#

One remarkable property of weak interaction is that they violate parity and charge conjugation, which are invariance principle that were considered central in physics until the 1950s. To understand the implications of this violation principle we need to first discuss symmetries and how they relate to physics.

Without invariance principles, there would be no laws of physics! We rely on the results of experiments remaining the same from day to day and place to place. An invariance principle reflects a basic symmetry, and is always intimately related to a conservation law (and to a quantity that cannot be determined absolutely). The proofs presented here rely on some key results from quantum mechanics.

Some classical invariance principles are related to the nature of space-time. We start by looking at continuous symmetries, such as invariance under space and time translation. These will be discussed also in your other quantum mechanics courses. We then move on to discuss invariance under discrete symmetries, which is at the core of particle physics.

6.5.1. Hermitian operators#

The first assumption we make is that operators corresponding to a physical observable in quantum mechanics are Hermitian, e.g. for any wave function we can write

Among physical observables, we should include the Hamiltonian \(\widehat{H}\) of a system.

6.5.2. Conserved quantities#

Next we show the important result that operators which commute with the Hamiltonian (the operator for total energy) correspond to quantities which are conserved, that is they are “constants of the motion”.

Consider an operator \(\hat{A}\) that does not depend on time, e.g. \(\frac{\partial \hat{A}}{\partial t}=0\), in this case the observed value of \(\hat{A}\) for a wavefunction \(\psi(x, t)\) is calculated as

And the derivative is

We now use the time-dependent Schrödinger equation and substitute

Showing that if the commutator of the operator \(\hat{A}\) with the Hamiltonian is zero, the observed quantities are invariant, which also means the eigenvalues of the operator are conserved quantities.

6.5.3. Translation invariance#

We now consider the translation operator \(D\) that moves the coordinate \(x\) by a quantity \(\delta x\). For simplicity, we consider only one spatial coordinate.

The Hamiltonian of an isolated system of particles that are not subject to external forces has to be invariant under this operator \(\widehat{D}\) as the physical laws should not depend on the where the observation is made. So we expect

We rewrite the wave function as a Taylor expansion after the translation:

Here we have used the notation where we indicate the exp of the partial derivative, which may look strange at first sight, but it is simply a shortcut for the Taylor expansion above. Using the Schrödinger equation and replacing in the formula

We get

As an expression for the translation operator. If the system is to be invariant under translation, this will apply for any value of \(\delta x\), and as a consequence we have

Which implies that the momentum is conserved as shown above.

Invariance of the Hamiltonian (the operator or expression for total energy) under a translation for an isolated, multiparticle system leads directly to the conservation of the total momentum of the system.

Example 6.2 Show that for a plane wave the momentum is conserved under the operator \(\widehat{D}\)

6.5.4. Generators#

In mathematical terms, we say that the translation operators \(\widehat{D}\) form a group and the operator \(\hat{P}_{x}\) is its generator. We will not discuss group theory here, but this result may be familiar to some of you.

Likewise it is easy to show that the time evolution operator

Can be expressed as

Which means that the Hamiltonian operator is the generator for the time evolution

Finally, the invariance of a system under rotation leads to the conservation of the angular momentum.

6.5.5. Parity operator#

The above continuous transformations led to additive conservation laws - the sum of all charges or momenta is conserved. There are also discrete or discontinuous transformations, which lead to multiplicative conservation laws. An important group of these are parity P, charge conjugation C and time reversal T .

The parity operator inverts spatial coordinates. It therefore transforms \(\underline{x}\) into \(-\underline{x}, \underline{p}\) into \(-\underline{p}\) etc. In other words, polar vectors change sign; axial vectors, such as angular momentum \(\underline{J}\), do not.

Now

The parity operator thus has eigenvalues of \(\pm 1\).

If \(\quad P \psi(\boldsymbol{x})=+\psi(\boldsymbol{x})\) the wavefunction has even parity, while if \(\quad P \psi(\boldsymbol{x})=-\psi(\boldsymbol{x}) \quad\) it has odd parity.

(Note that wavefunctions do not have to be eigenfunctions of parity.)

The spherical harmonics \(Y_{l}^{m}(\theta, \phi)\) (met in atomic physics and elsewhere) are examples of eigenfunctions of the parity operator. (If they are not familiar, look them up!) By considering a reflection in the origin, it should be clear that in spherical polar coordinates, the parity operator causes

and by inspection of the form of the spherical harmonics it can be seen that \(Y_{m}^{l}(\theta, \phi)\) changes sign if \(/\) is odd and remains the same if it is even,

i.e.

Since particles can be created in interactions, it is important to assign an “internal” parity to each particle, as we will see pions have parity -1 , while a fermion-antifermion pairs have opposite parity.

Electromagnetic and strong interactions conserve parity, and invariance with respect to \(P\) leads to multiplicative conservation laws.

E.g. Consider \(\quad a+b \rightarrow b+c\)

The initial state wavefunction can be written as \(\psi_{i}=\psi_{a} \psi_{b} \psi_{l}\), where \(\psi_{a}\) and \(\psi_{b}\) are “internal” wavefunctions for particles a and b , and \(\psi_{l}\) is the wavefunction describing their relative motion which depends on the angular momentum I. The P operator affects each factor, so \(P \psi_{i}=P \psi_{a} P \psi_{b} P \psi_{l}\)

If the intrinsic parities of the particles are given by \(P \psi_{a}=\pi_{a} \psi_{a}\), etc., where \(\pi_{a}\) is just a number \(\pm 1\), then

i.e. the parity of a multiparticle system is given by the product of the intrinsic parities of the individual particles and the parity of the wavefunction describing their relative motion.

6.6. Parity of the pions#

As discussed earlier, particles have an intrinsic parity, which needs to be taken into account when evaluating the parity of a system. Parity of particles is determined experimentally by measuring the relative parity of a particle compared to the known parity of other particles. Since this is a relative measurement, we assume that the parity of protons and neutrons is +1 and derive the rest from experiment.

6.6.1. Pion capture process#

Here we show how we can determine the parity of the \(\pi^{-}\)to be -1 . We use the pion capture process

Where a negative charged pion is captured by a deuteron. The \(\pi^{-} d\) system form a “mesic atom”, similar to a hydrogen atom, with the electron replaced by a pion. It is observed that the capture takes place in the atomic \(s\)-state with orbital angular momentum \(L=0\). Hence the parity of the initial state is the product of the pion and deuteron parity

Since the spin of the pion is zero and that of the deuteron is 1 , the initial state has total angular momentum \(J=1\) due to the composition of angular momenta.

Final state wavefunction

In the final state we have two neutrons, which are identical fermions and as such their wavefunction needs to change sign if we exchange the two particles (recall the property of fermions vs bosons). The wave function can be written as the product of a space and spin parts

Where we indicate with \(\psi(\boldsymbol{r})\) a function of the relative coordinate of the neutrons in the centre of mass system and the spin state is identified by the spin length and its zcomponent.

6.6.2. Spin of the final state#

The two neutrons have spin \(1 / 2\), so they can combine into 4 different states, 3 states with total spin 1 and one state with spin 0 :

Where the notation on the right-hand side refers to the z-component of the spin of the neutrons. It can be noted that the three states with spin 1 are symmetric if we exchange the two neutrons, while the state with spin 0 is anti-symmetric for particle exchange.

In conclusion the exchange of the two particles will result in a change of sign in the wave function given by \((-1)^{S+1}\)

6.6.3. Orbital momentum of the final state#

In the centre of mass frame the position of the two neutrons is \(r\) and \(-r\), respectively. The angular dependency of the wavefunctions is given by the spherical harmonics \(Y_{m}^{l}(\theta, \phi)\) and swapping the two particles is equivalent to a reflection in the origin, and so the change in the wavefunction is given by \((-1)^{L}\) where \(L\) is the orbital angular momentum of the final state. Therefore the exchange of the two neutrons will result in a change of sign of the wavefunction given by the product of the two \((-1)^{L+S+1}\). Since we expect the state to be anti-symmetric, we conclude that \(L+S\) has to be even.

Angular momentum conservation in the reaction, implies that the total angular momentum \(J=1\) is conserved. Using the rules for the addition of angular momenta, we can only have the following possible final states:

The only combination with \(L+S\) even is when \(L=1, S=1\). Which is the angular momentum of the final state.

Parity of the final state, conclusion

Now that we know the momentum of the final state, we can evaluate its parity as

(Note that the parity of the neutron is irrelevant here, since its square is always +1 ) Putting it all together we have

The deuteron is bound state of a proton and a neutron, which both have parity +1 in a state with orbital angular momentum 0 , so \(P_{d}=+1\)

In conclusion the parity of the pion is \(P_{\pi}=-1\)

(Note that this result is independent on the value we assigned to the parity of the proton and the neutron!)

6.6.4. Parity of particle-antiparticle systems#

An important experimental result, which we will not discuss here, is that the parity of a fermion and that of its corresponding antifermion is opposite. Differently a boson and its corresponding antiparticle have the same parity, for instance the \(\pi^{-}\)and \(\pi^{+}\)particles.

In the following we will use the notation \(J^{P}\) to indicate the spin and parity of a particle or a system of particles. Where \(J\) indicates the total angular momentum (e.g. the spin for a single particle) and \(P\) the parity. So for the pion we write \(J^{P}=0^{-}\), for the proton and neutron \(J^{P}=\frac{1}{2}^{+}\)

Example 6.3. Parity of the \(\rho\) particle

The \(\rho\) meson has spin 1 and decays into a pair of pions \(\rho \rightarrow \pi^{+} \pi^{-}\). What is its parity?

Solution

The \(\rho\) is a particle with spin one decaying into two particles with spin zero. We apply conservation of angular momentum. In the initial state the total angular momentum is 1 (due to the spin of the \(\rho\) ). In the final state the pions have no spin, so to conserve angular momentum the orbital component of the angular momentum has to be one ( \(L=1\) ). In conclusion the parity of the \(\rho\) is

(We should note that the result is independent on the parity of the pion, since that quantity is squared.)

6.7. Charge conjugation#

Another discrete transformation is charge conjugation, \(\hat{C}\), which changes a particle into its antiparticle. This reverses the charge, magnetic moment, baryon number and lepton number of the particle. Neutral states and neutral particles can be eigenstates of the \(\hat{C}\) operator. For instance the photon is an eigenstate of \(\hat{C}\) with value -1 :

Which can be derived from the Maxwell equations and the fact that electromagnetic fields are generated by moving charges that change sign under \(\hat{C}\).

The charge conjugation is a multiplicative number, such as the parity, and it is easy to show that \(\hat{C}^{2}=1\).

6.8. Parity violation in weak interactions and neutrino helicity#

One important result is that both C and P are conserved in electromagnetic and strong interactions. The same is not the case in weak interaction. This is experimentally observed in nuclear physics as decays between different parity states are observed.

This violation comes from a basic principle in particle physics, which is the fact that the projection of the spin of a neutrino in the direction of its motion is always negative. We call this quantity the helicity

which is illustrated in the diagrams of Fig. 6.6 . We observe that neutrinos are always lefthanded ( \(h=-1\) ) while antineutrinos are always right-handed ( \(h=+1\) ).

Fig. 6.6 Possible spin configurations for the neutrino and antineutrinos#

The parity operator will change the momentum of a neutrino, but not its spin, so under parity operation the left-handed neutrino would turn into a right-handed neutrino. Right-handed neutrinos are not observed in Nature, which means that weak interactions cannot be invariant under parity.

On the other hand the C operator will change a neutrino into an antineutrino. The application of both the C and P operators to a neutrino state will result into a right-handed antineutrino. So the expectation is that weak interactions are invariant under the \(C P\) operation combined.

(Note: small violation of the CP symmetry are observed, so this is not the end of the story. We stop here for now. But a violation of CP symmetry results in an asymmetry of matter vs antimatter which may explain why the Universe is predominantly made of matter!)

6.9. Further reading#

Most of the material on weak interactions is taken from [Perkins] sec 2.8

A more in-depth treatment of beta decay can be found in [Perkins] sections 7.2, 7.3, 7.4

Some experimental results are also found in [Perkins] section 7.11 and 7.12

Parity and charge conjugation are defined in [Martin] section 1.3.1

The spin and helicity of neutrinos is discussed in [Martin] section 6.3

The parity of the pion is discussed in [Martin] section