3. Fermions, bosons and interactions#

Learning objectives:

understand the difference between fermions and bosons, and how they behave.

be familiar with the consequences of boson exchange in the mediation of forces

In this unit we introduce the elementary particles that make up the Standard Model of particle physics. We define their property using quantum mechanics, and how particles interact with each other by exchanging quanta of information (e.g. other particles).

3.1. Fermions and Bosons statistics#

A multi-particle wave function for non-interacting (e.g. widely separated) particles can be written as the product of single particle functions. For instance, for a system of three particles

where \(A, B, C\) describe the quantum states and the numbers \(1,2,3\) are labels to identify each of the particles. (c is simply a normalisation constant). All the observables for this quantum state are related to the square of the wave function \(|\Psi|^{2}\).

If we consider a system of identical, indistinguishable particles, then interchanging a pair of particles is unobservable, e.g.

In other words, if the three particles are identical, we can only state that we have a particle in state \(|A\rangle\), one in state \(| B\rangle\) and one in state \(| C\rangle\) but we can not distinguish which one is in which state. The total wavefunction can either remain the same or change sign when two identical particles are swapped, e.g.

These two cases have important physical consequences. If two particles are in an identical quantum state \(| A\rangle\) then we can have either

\(\Psi(1,2)=c \Psi_{A}(1) \Psi_{A}(2)=c \Psi_{A}(2) \Psi_{A}(1)\)

\(\Psi(1,2)=c \Psi_{A}(1) \Psi_{A}(2)=-c \Psi_{A}(2) \Psi_{A}(1)\)

The first case can be satisfied by any value of \(c\), the second case is only satisfied if \(c=0\), e.g. if the wavefunction is zero. Particles obeying the two conditions have completely different behaviours, as they can (or cannot) occupy the same quantum states

Bosons

Bosons have wavefunctions which are symmetric under the interchange of identical particles. They obey the Bose-Einstein statistics, showing constructive interference of identical single particle wavefunctions. Writing down a wavefunction which is guaranteed to be symmetric under the interchange of 1 and 2 we have

Bosons have integer spin, i.e. \(0, \hbar, 2 \hbar, \ldots\) And include particles such as the photon \((\gamma)\), pios \((\pi)\) and other mesons. They include the quanta of fields, i.e. the carriers of forces \(W^{ \pm}, Z\), gluon. Bosons can be created and destroyed in any number e.g.

Bosons can be their own antiparticles e.g. the neutral pion \(\left(\pi^{0}\right)\)

Fermions Fermions have wavefunctions which are antisymmetric under the interchange of identical particles. They obey the Fermi-Dirac statistics, showing destructive interference of identical single particle wavefunctions. In particular, no two identical fermions can occupy states with identical quantum numbers. The antisymmetric combination is

Fermions are particles with “half integer” spin, i.e. \(\hbar / 2,3 \hbar / 2,5 \hbar / 2, \ldots\) They include the constituent particles of matter such as the proton, neutron, electron, neutrino, quarks, among many others. For each particle, there is a distinct antiparticle, e.g.

In particular the neutrino and antineutrino are both neutral, but are different particles. Fermions obey conservation laws, and they are only produced as fermion-antifermion pairs.

3.1.1. Fundamental particles (fermions)#

The fundamental fermions are leptons, which are electron-like particles, and the quarks. They all have spin \(1 / 2\) and are grouped in 3 families as shown in left columns in the picture at the front of your handbook.

Leptons

Each lepton family has an associated lepton number which is (as far as we know) absolutely conserved. The lepton number \(L_{e}\) is defined as +1 for particles and -1 for anti-particles for the first lepton family this is

\(L_{e}=1\) for the electron \(e^{-}\)and the electron neutrino \(\nu_{e}\)

\(L_{e}=-1\) for the positron \(e^{+}\)and the electron antineutrino \(\bar{\nu}_{e}\)

Each lepton generation has its own distinct lepton number, \(L_{e}, L_{\mu}, L_{\tau}\). This is what makes the different neutrinos distinct, and forbids decays as \(\mu^{-} \rightarrow e^{-} \gamma\).

Charged leptons have increasing mass with the increasing family number: The mass of the electron is \(0.511\ \mathrm{MeV} / c^{2}\), the mass of the muon is \(105.7\ \mathrm{MeV} / c^{2}\) and the mass of the tau is \(1777\ \mathrm{MeV} / c^{2}\). The neutral leptons (neutrinos) are known to have a mass, but the mass has not been directly measured yet. The measurement of the neutrino masses and their differences is a major research topic in particle physics.

Quarks

Similarly quarks are grouped in 3 families with a fractional charge of \(+2 / 3 e\) for the up, charm and top quarks and \(-1 / 3 e\) for the down, strange and bottom quarks. Quarks have antiparticles called antiquarks with opposite charge. Quarks do not exist in isolation, but always combine in groups of two or three to form hadrons. There are hundreds of known hadrons and we will learn how to classify them at the end of the semester. For now it is sufficient to know that particles made of a quark-antiquark pair are called a mesons and have integer spin, while particles made of a group of three quarks (or three antiquarks) are called baryons and have half-integer spin. Pions are examples of mesons (with spin 0) and the proton and the neutron are examples of baryons (with spin \(1/2\)).

The interaction of quarks from different families is allowed by the weak interaction, so there is only a global baryon number \(B\). Quarks have \(B=+1 / 3\), antiquarks have \(B=-1 / 3\). For instance

The proton is made of two \(u\)-quarks and one \(d\)-quark (\(uud\)) and has baryon number \(B=1\). Likewise the neutron is made of \(u d d\) quarks and also has baryon number \(B=1\)

The antiproton is made of \(\bar{u} \bar{u} \bar{d}\) and has baryon number \(B=-1\), similarly the antineutron has \(B=-1\)

The \(\pi^{+}\)is made of \(u \bar{d}\) and has \(B=0\), similarly the \(\pi^{-}\)and \(\pi^{0}\) and all other mesons have \(B=0\)

Quarks have an additional quantum number, which is called “colour”, we will be discussing quarks and their property in a later section.

Example 3.1.

Example of allowed and forbidden decays

Which of the following decays is allowed (or not) and why:

\(\mu^{-} \rightarrow e^{-} \gamma\)

\(\mu^{-} \rightarrow e^{-} \bar{\nu}_{e} \nu_{\mu}\)

\(\pi^{+} \rightarrow \mu^{+} \nu_{\mu}\)

\(p \rightarrow \pi^{+} \gamma\)

\(\pi^{+} \rightarrow \gamma \gamma\)

\(\pi^{0} \rightarrow \gamma \gamma\)

\(\pi^{+} \rightarrow \tau^{+} \nu_{\tau}\)

Solution

\(\mu^{-} \rightarrow e^{-} \gamma\) is not allowed. The muon and electron lepton numbers are NOT conserved

\(\mu^{-} \rightarrow e^{-} \bar{\nu}_{e} \nu_{\mu}\) is allowed. Muon and electron lepton numbers are conserved

\(\pi^{+} \rightarrow \mu^{+} \nu_{\mu}\) is allowed. Muon number is conserved, baryon number of is zero

\(p \rightarrow \pi^{+} \gamma\) is not allowed. The baryon number is NOT conserved

\(\pi^{+} \rightarrow \gamma \gamma\) is not allowed. Charge is NOT conserved

\(\pi^{0} \rightarrow \gamma \gamma\) is allowed. There are no leptons and the baryon number is zero

\(\pi^{+} \rightarrow \tau^{+} \nu_{\tau}\) is not allowed. Energy is NOT conserved as the tau is heavier than the pion

3.1.2. Fundamental particles (bosons)#

To complete the picture of the fundamental particles shown in the front page of the booklet, we should mention the gauge bosons as fundamental particles. Gauge bosons are carriers of fundamental forces and mediate interaction between other particles (and themselves in some cases). In particular

The electromagnetic force is mediated by the photon, which is indicated with the symbol \(\gamma\) and has zero mass;

The strong force is mediated by the gluon, indicated by \(g\), also with zero mass. There are 8 different types of gluons characterised by different colour pairs;

The electroweak force is mediated by the \(Z^{0}\) and \(W^{ \pm}\)bosons. These have a large mass and are charged (the \(W\)’s) or neutral \((Z)\).

Finally, the Higgs boson plays a particular role in particle physics to provide mass to all the other particles.

All the particles described in this section, and illustrated in the front page of the booklet, are the fundamental particles of the Standard Model of Particle Physics. Their role in shaping the world around us will be the main topic of this course!

3.2. The Yukawa potential and interaction range#

Interactions in physics are mediated by bosons, the familiar example is that of electromagnetic interactions that are mediated by the photon. Before we move on to classify the different interaction mechanisms in particle physics, we discuss how interactions potentials depend on the mass of the mediator.

In Section 2, we have considered interactions of particles with an electrostatic potential. This interaction is mediated by a massless photon. Here we derive the potential for interactions mediated by a massive particle, such as the \(W\) and \(Z\) boson that mediate the weak interactions, and we will show how different physics behaviour is expected. For a particle with mass, the relativistic equation \(E^{2}=p^{2} c^{2}+m^{2} c^{4}\) can be converted into a wave equation by the substitutions

Hence

In the static, time independent case, this leads to

(which in the case \(m=0\) leads to the differential equation for a static electromagnetic potential, as expected)

The expression for the \(\nabla^{2}\) operator in spherical coordinates can be found in literature, as well as on the ancillary material of your exam papers. In the case of point source with spherical symmetry, with no dependency on the polar angles \(\theta\) and \(\phi\) the differential operator can be written as

so the equation turns into

with solution

where \(g\) is a constant called the coupling strength and \(R=\hbar / m c\) is the range of the force. This is known as the Yukawa form of the potential and was originally introduced to describe the nuclear interaction between protons and neutrons due to pion exchange.

Using this form of potential and the Born approximation in equation (2.10), after some manipulation (see Exercise A2), we get the matrix element

It can be noted that for a massless propagator with \(m=0\), we return to the situation for electromagnetism, where the range of the force \(R \rightarrow \infty\) and the cross section is proportional to \(1 / q^{4}\)

Example 3.2. Weak interactions range

Calculate the range of the Weak force mediated by an exchange of a \(W\) boson of mass \(80\ \mathrm{GeV} / \mathrm{c}^{2}\).

Solution

The range is given by the expression above:

Which is much shorter than a typical nuclear radius, which means that the weak force is “weak” at the distance scale of nuclear physics \(\left(10^{-15}\ \mathrm{~m}\right)\), and it becomes important when we start probing distances three order of magnitude smaller than the nucleus.

3.3. Interactions and fields#

Quantum field theory describes interactions at very small distances. The quantum nature of the interaction makes it necessary to abandon the continuous potential model, and we must regard the interaction as being propagated by individual quanta (bosons) which are specific to the type of interaction. (This is known as second quantisation).

In modern field theories, we have the fundamental forces acting between fermions and transmitted by the exchange of bosons (particles of spin \(0,1,2, \ldots\) ). As an example in electromagnetism electrons (spin \(1/2\) fermions carrying a charge) interact via the exchange of photons (spin \(1\) neutral bosons). However, in quantum field theory, the role can be reversed and both fermions and bosons can be exchanged in an interaction, as we no longer work with particles and fields, but rather with particle wavefunctions.

The four fundamental forces are electromagnetism, the weak force responsible for nuclear beta decay, the strong (nuclear) force and gravity. Their properties are given in the table below.

Interaction |

Source |

Particle. |

Spin |

Mass \((\mathrm{GeV})\) |

Strength |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Strong |

“colour” |

Gluon \((g)\) |

1 |

0 |

\(<1\) at \(R>10^{-15} \mathrm{~m}\) |

E.M. |

Charge |

Photon \((\gamma)\) |

1 |

0 |

\(\approx 10^{-2}\) |

Weak |

Leptons |

\(W^{ \pm}\)and \(Z^{0}\) |

1 |

\(80-90\) |

\(\approx 10^{-13}\) at \(R=10^{-15} \mathrm{~m}\) |

Gravity |

Mass |

Graviton \((G)\) |

2 |

0 |

\(\approx 10^{-38}\) |

Gravity is of great importance between macroscopic bodies (like us and the Earth) is too weak to play an important role between fundamental particles. We will only make one remark: that the spin of the graviton (2) is related to the fact that there is only positive mass, so dipole radiation is not a possibility.

Weak has a short range of interaction, as we discussed when deriving the Yukawa potential. The interaction is only “weak” at a distance above \(10^{-18}\ \mathrm{~m}\) due to the mass of the force mediators, and at the nuclear scale this interactions is weaker than the strong interaction that keeps the hadrons together. The weak interaction is responsible for nuclear decays, however at very short distances, it is no weaker than electromagnetism. Note that all fermions (including neutrinos) experience the weak interaction.

Electromagnetism is the everyday force responsible for chemistry, solid state physics, friction and the stability of atomic matter in general.

Strong interaction was originally postulated to bind protons (and neutrons) together in nuclei against the large electromagnetic repulsion. We now know that this is a second-order effect similar to the Van der Waal’s (electromagnetic) force which binds neutral covalent molecules in solids. The strong interaction is responsible to bind the quarks together in hadrons due a “colour charge” which we will study later in the course. The colour has nothing to do with the normal colour of an object! And protons and neutrons are “colourless” quark combinations.

In this course, we will examine three of the forces (excluding gravity) in some detail. However, we will first look at the general properties of interactions mediated by the exchange of bosons, before returning to each type of interaction in turn.

3.4. Feynman diagrams#

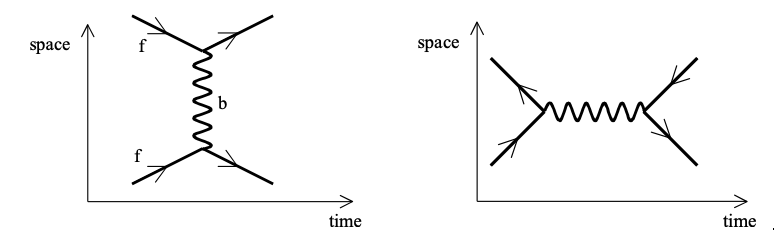

To represent the interaction of particles in quantum field theory we use Feynman diagrams. The theoretical foundation behind Feynman diagrams is beyond the scope of this course. These are simply seen as a graphical representation of the matrix elements, which can be calculated using mathematical rules. Feynman diagrams are drawn in a space-time cartesian graph, and arrows are drawn on fermion lines with particles propagating “forward” in time and anti-particles propagating “backwards” in time. We will use many Feynman diagrams in this course as they give a simple graphical representation of what would be a very complex mathematical description.

As an example, fermion-fermion scattering can then be represented diagrammatically as shown in Fig. 3.1 (left). These diagrams have special space-time properties. If twisted or rotated they reveal intimately related processes, as shown in Fig. 3.1 (right). In this case, we must interpret a “fermion going backwards in time” as a normal antifermion. This diagram therefore shows a fermion-antifermion pair annihilating to produce a (virtual) boson, which then materialises as a new fermion-antifermion pair.

Fig. 3.1 Feynman diagrams representing the interaction between two fermions. The diagram on the left represents the scattering between two particles, while the diagram on the right represent the annihilation of a particle with its corresponding antiparticle.#

You may notice that energy is not conserved at each of the vertexes represented in the diagram. The interaction happen over a short period of time, and the uncertainty on the energy exchanged in this time period obeys the Heisenberg principle \(\Delta E \Delta t \approx \hbar\). However, it is important to point out that energy is conserved between the initial and final state.

We will represent all the interactions between particles with the aid of Feynman diagrams, and introduce lines for each particle in the Standard Model. Each Feynman diagram is the graphical representation of a matrix element \(\mathcal{M}_{f i}\), and the mathematical expression can be calculated using rules derived in quantum field theory. The matrix elements from diagrams corresponding to the same final state need to be added and then squared to calculate a cross section or a transition between initial and final states. We will not go into the mathematical details for the Feynman rules, and we will limit ourselves to understand the relative order of magnitude of each diagram. The exact calculation of Feynman diagram is the topic of a more advanced course in particle physics.

3.5. Further reading#

Interactions, Feynman diagrams and the Yukawa potential can be found in Sections 1.4 and 1.5 of [Martin]

Fermions and bosons are discussed in [Perkins] Section 1.3

Lepton and baryon numbers are discussed in [Perkins] Sections 1.7 and 1.8 and in [Martin] sections 3.1 and 3.2